National Palace Museum Treasures During the War

Chinese Citizens and Chinese Treasures Moved Inland to Escape the Japanese

Chinese were fleeing ahead of the advancing Japanese forces. Students and professors, in fact almost whole universities, were moving west. Teaching equipment, books, even laboratory equipment was moved. Peking and Tsinghua Universities from Beijing and Nankai University from Tianjin moved first south to Changsha and then on to Yunnan province in southwest China. They then formed the National Southwestern Associated University during the war. For that last part, from Hunan province to Yunnan, students and professors walked 1600 kilometers in 68 days.

Countless families made similar journeys, trying to move towards safety, or at least relative safety.

Japanese bombers also flew further and further west, bombing Chinese targets. At the beginning of the war, the Chinese air force resisted as best they could. But the Japanese air force was stronger and over time the Chinese fighter planes were shot down or crashed and the Japanese gained control of the skies.

Along with the government and educational institutions, and countless Chinese individuals and families, so too did the imperial treasures of the Palace Museum, also known as the Forbidden City. I want to share the story of their incredible journey to help you understand the journeys that many Chinese made seeking safety in the face of the Japanese advance. The story of the treasures is also the story of China and of the Chinese during the war. There was a conscious effort to outlast the Japanese advance, to preserve China, Chinese people, and Chinese culture. There was a belief that Japan might have success in the short run, but that China would endure. It did. And so did the treasures. This is the story of their journey west, away from the Japanese advance.

In 1912, when the boy Puyi abdicated as emperor, creating the Republic of China, he was allowed to continue to reside in the Forbidden City. In 1924, following a war between the Anfu and Zhili Cliques, the Christian Warlord Feng Yuxiang gave Puyi and his entourage three hours to leave. Never again would the Forbidden City be a home.

Cynics assumed that Feng would loot the imperial treasures and sell them. But instead, the new government cabinet ordered an inventory. Each room was locked and sealed and a committee of scholars, mostly from Peking University, began the arduous task of identifying and documenting every jade, book, painting, piece of jewelry and bronze. It started in December 1924. They worked in sub-freezing temperatures.

Na Chih-liang was barely 17 years old and had recently finished high school. As the youngest, he was assigned the task of recording what the more experienced investigators told him about the art. The only problem was that his ink jar was frozen solid. His complaints fell on deaf ears, and he was told to put the writing brush in his mouth to warm it up enough to get a bit of ink to describe each piece. He would suck on his brush, taste the ink and feel the cold.

Some of the works were masterpieces. Like Early Snow on the River from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, after the collapse of the Tang. It’s a handscroll twelve feet long and a thousand years old. It is meant to be unrolled and viewed from right to left, a bit at a time. It tells a story as your eye moves from right to left. It leaves the viewer with a completely different experience than western paintings that are generally meant to be viewed all at once from only one position.

One of the supervisors was Professor Ma Heng. He had earned the highest Jinshi degree under the old Imperial Examination system. He came from Shanghai. His father was a rice trader who rose up to become a government official by serving the Qing during the Taiping Rebellion. Ma Heng was studious and engaged at age 12 to the daughter of a wealthy Shanghai businessman. His father-in-law had the license to represent John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil in China and led the distribution and sale of kerosene lamps throughout China. When Ma Heng was fourteen and engaged, his father died and he was taken in by his future in laws. He later married, as planned and then, contrary to Chinese norms, moved in his with in-laws and joined their family business. He eventually returned to his true passions by becoming a Professor at Peking University. He loved antiquities and both studied them professionally and bought them personally. He was an avid collector.

In 10 months, the team documented over 1 million objects in the Forbidden City. The government decided that on October 10, 1925, on the 14th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution, the Forbidden City would be opened to the public as the Palace Museum. When the decision was made, that was only a week and a half away. So, the team then rushed to get the collection ready for the public.

There was such a crowd when the Palace Museum opened that it was tough to see the treasures. So many people were filing through for the first time, that the crowd just kept pushing people along. If you were lucky, you could glimpse an object as you moved past, almost as if propelled by a conveyor belt of human beings.

Ma Heng was busy advocating for modern practices at archaeological sites and against the removal of antiquities from China by foreigners, and against looting by Chinese. He bravely confronted one warlord after Qing tombs southwest of Beijing were looted. He tipped off authorities as the objects started to be sold in markets. That warlord, Sun Dianying, sent men after Ma Heng and he had to hide out in Tianjin and then Shanghai for a while. A few weeks later, this bookish professor in glasses was able to return to Beijing.

After Chiang Kai-shek succeeded in forming a national government after the Northern Expedition, China’s capital became Nanjing, rather than Beijing. And beginning in 1931, Japan took control of Manchuria, just northeast of Beijing, and set up the puppet state of Manchukuo. Now Japan was acting aggressively just a short distance from Beijing. In 1932, during Japan’s first attack on Shanghai, the Oriental Library was bombed and burned to the ground. Half a million documents, including rare books and maps, were lost from the archives.

It was then, by 1932, that the decision was made to move the fragile collection of the Palace Museum out of the Forbidden City. If war came to Beijing, it would be too late.

Moving the entire collection of more than 1 million pieces was not feasible. So, curators decided to focus on the most significant and irreplaceable items. The team that packed up the treasures was virtually the same as those who had done the inventory 8 years earlier.

Through trial and error, they learned how to pack the items tightly and separately, using cotton, rice husks, paper and cord to secure the items inside packing crates. Chuang Yen was one of the team and his family name sounds like the verb to pack. So, he became Old Mr. Packer. Over 13,000 cases were packed at the Palace Museum, with additional cases from other museums and archives.

To raise funds, the Museum Director ordered that objects with no historical or artistic significance be sold. But that created an uproar. The public believed that national treasures were being sold off. Confidence in the moving project fell. Rumours started going around that the antiquities would be transferred to western banks in exchange for foreign loans. That was not true, but it caused countless problems. The porters hired to transport the crates to the railway refused to work and just shifted items from one part of the palace to another. There were even bomb threats against the train.

On January 1, 1933, the Japanese attacked the Chinese garrison guarding the town where the Great Wall reached the sea. Within days, the Japanese held this vital point, including the railway connection south and to Beijing.

There was fear of a Japanese invasion. But transportation companies refused to help, since they had no confidence that the treasures wouldn’t be sold.

It took requisitioning military trucks to get the job done and 2000 police secured roads. The crates were moved overnight and onto freight cars heading south. It was February 1933 and none of the treasures would return to Beijing for at least sixteen years. Some never have and now are on display in Taipei.

Among the items was the Complete Library of Four Branches. That was a collection by the Qianlong Emperor, the longest serving of the Qing. It collected the important works of the Four Branches of scholarship: classics, histories, philosophy, and literature. They totaled 79,000 volumes. By 1933, only four copies remained in the world, and one was on the train.

As the locomotive travelled south, the organizers worried about bandits. Each carriage had a machine gun on its roof and had armed police. When the train stopped to load coal or water, troops on horseback patrolled. They heard a frightening rumour that at one stop, Xuzhou, there could be 1000 bandits. But the security measures worked and the train proceeded safely to Nanjing.

An issue was how to warehouse them. Moisture, humidity or fire could all be ruinous. A suitable location was found. A disused seven-story hospital in the French concession of Shanghai was rented. But there were delays and debates because of the optics of these national treasures going to French territory. After delay, they proceeded by boat from Nanjing to Shanghai.

More shipments from Beijing followed.

Ma Heng ordered his team to go to the Imperial Academy in Beijing, a center of Confucian learning during the Ming and Qing dynasties. They were to pack up the Stone Drums of Qin. Each is about two feet wide and two to three feet high, made of granite. They look like Chinese drums and are very heavy. But their value comes from the inscriptions on them. Each drum contains a poem in an early version of Chinese characters. They may be from the Zhou period. That makes them well over 2000 years old and roughly from the same time as Confucius, Mencius and Sun-tzu, who wrote the Art of War. History has reduced the number of drums left. And scholars over the years did rubbings in a way that caused many inscriptions to flake away. The remaining ones are indeed precious.

Ma Heng researched the best way to preserve them for transportation. It was a painstaking process of filling cracks and fissures with a wet paper that when dried, acted like cement. The porters hated moving these granite drums.

By mid 1933, five shipments totaling 20,000 cases had moved south. Then the Director of the Palace Museum was forced out from the scandals and rumours surrounding the project. Ma Heng took over and ordered a new inventory to ensure accurate records.

To deal with these political issues and suspicions about national treasures leaving the country, a permanent home in the capital, Nanjing, was planned. It would have air conditioning with a secure, hidden vault, under a hill, secure against bombing or theft. In December 1936, while Chiang Kai-shek was kidnapped, the Nanjing location was ready, and the 20,000 cases moved from Shanghai to Nanjing.

Then, as you know from last episode, the Japanese attacked, first by the Marco Polo Bridge outside Beijing. Then Shanghai and in December 1937, Nanjing as well.

These national treasures would not be safe in Nanjing. As soon as the attack on Shanghai began, the guardians of these imperial treasures went to work seeking a new home for them. Shanghai was simply too close to Nanjing. They knew war was coming to the capital.

The most significant objects would need to move west immediately. The others were placed in the underground vault, to protect them from bombing.

The most precious 80 cases went by steamship to Changsha, capital of Hunan province. One curator, Old Mr. Packer, went along with his wife and their three children.

The very next day, the Japanese bombed Nanjing for the first time. China still had its air force and the Chinese fighters, including Curtiss Hawk II biplanes, shot down 4 Japanese Mitsubishi G3M bombers.

The steamship took 4 days to get from Nanjing to Wuhan, on the way to Changsha. The team thought this too slow, so the precious cargo continued by train from Wuhan to Changsha. That meant unloading them, loading them onto a ferry across the Yangzi River and then by porter onto a train. Each step was dangerous. They made it safely to the university library in Changsha.

Old Mr. Packer, with his family, was allowed to stay there. But another staff member, the former 17-year-old who had to taste frozen ink, Na Chih-liang, was ordered back to Nanjing. The main train station in Changsha was a melee of people fleeing the Japanese. “Mountains and seas of people”, he wrote. Some were heading west. Some were heading east, trying to board a boat to leave China altogether. He couldn’t even get close to the ticket counter to pay the fare for the train. He wandered around outside instead. He met a captain of a cargo ship, who sold him passage east, even including a cabin to sleep in.

The situation in Wuhan was even more chaotic. He couldn’t find a berth. He had to strike an illegal deal with deckhands, who smuggled him below deck. He had to stay on a bunk, behind a curtain and not show himself under any circumstances. A custom inspector came on at one point, and all the people like Na were silently moved around the ship until the inspector left.

At Nanjing, the situation was even worse. The captain wouldn’t even try to dock. Anyone wanting to get off the boat would have to do so in the middle of the mile wide Yangzi and make his own arrangements!

Luckily, little skiffs approached the ship and the boatmen negotiated stiff prices to take passengers to shore. They threw rope ladders up. Anyone wanting to leave had to climb down a rope ladder into a tiny skiff and pay whatever was demanded.

Unlike many of the refugees, the Palace Museum staff were still being paid. At least they had their salaries.

But over the course of the war, inflation would eat heavily into fixed salaries, like those of government employees.

At the beginning of the war, the Republic of China still had regular tax revenues and was able to borrow money both internationally and at home through war bonds. Banks were able to operate in the foreign concessions in Shanghai, which were not occupied by the Japanese until late 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor and corresponding attacks in east Asia on American and European holdings.

As the war ran on, Japan captured more Chinese land and ports, and devastated cities, railways, bridges and industry by bombing. This lessened Chinese production and income to tax. The Nationalist government relied more on more from loans from the four Chinese banks that it controlled, which in turn were allowed to print bank notes. The government didn’t print money directly, the banks they controlled did. One source I read, published in 1940 explained that for every Yuan 100 of additional bank notes issued, Yuan 40 could be borrowed by the Treasury from those banks. If that is correct, then the bank notes increased 2.5 times as fast as the government war deficit.

Over time, lack of confidence in the value of money meant that people wouldn’t save it. They would spend it as soon as they received it, assuming it would go down in value if they held it. That worsened inflation even more.

And the end of the war didn’t improve that situation much. The economy was still heavily damaged from the war and the Civil War between the Communists and the Nationalist government started soon after Japan’s defeat. Government military expenses didn’t decrease once Japan was defeated. Expenses continued to rise as Chiang Kai-shek kept the military mobilized in the civil war.

Returning to the main story.

With the Japanese advancing on Nanjing, Ma Heng and the Palace Museum Directors decided that Changsha was too close and would not be safe. The objects there would need to continue to Guizhou. This became known as the Southern Route. That province was poor, remote and mountainous. The local people said that in their province “a sky never three days clear, land never three feet level, and people never three coins wealthy”. Railways and boats wouldn’t work. So, the treasures would need to travel by truck. The roads were unreliable and the route was roundabout. It would take 600 miles. But how to even get the trucks?

After a lot of effort, they rented three buses, a truck from the post office and vehicles form the Guangxi Provincial Roads Administration. The roads were so bad, it took more than two weeks to cover that distance of around 1000 kilometers. More cases followed a month later. By the time the crates arrived, Guizhou was already experiencing a population boom. Refugees from the east coast had arrived and the speech and tastes of those easterners was infiltrating this remote area. Restaurants were already offering dishes enjoyed by those easterners. Western style suits and high heels mixed with the locals and the colourful clothes of the Miao people, a minority group from mountainous areas of southwest China. Chinese were mixing and the war built a common national identity.

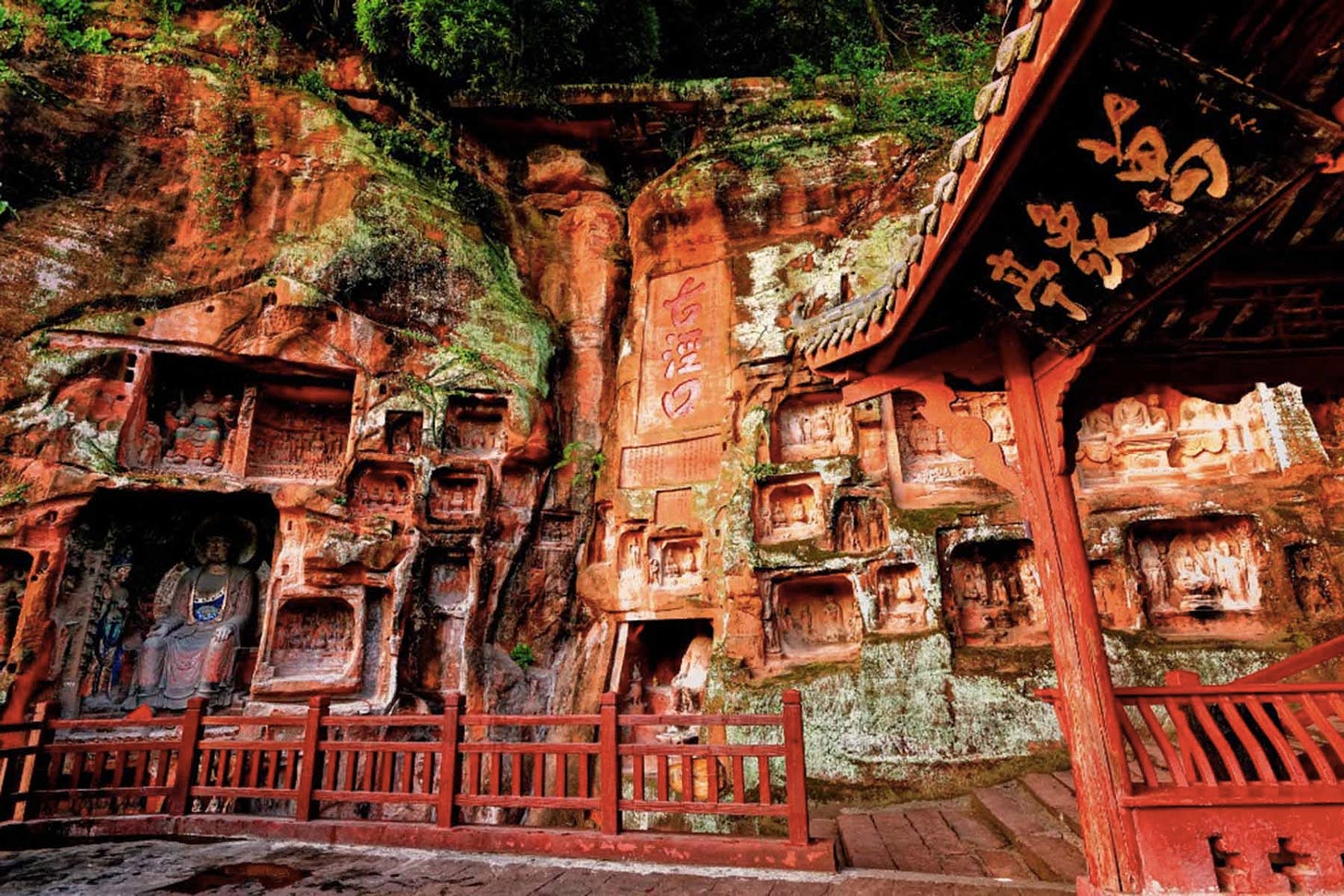

Ma Heng looked for the best cave for the treasures. The first one they were offered was small, narrow and tough to access and dripping wet. That wouldn’t do. Another one was on the top of a mountain. The porters would not be able to manage the steep climb safely. Eventually, they settled on a Buddhist temple guarding a cave. The monk was of questionable religious devotion. He had a wife and a side business slaughtering pigs. But the cave was spacious with a high domed roof. It wasn’t too damp and was accessible. The items were moved there, to a cave in Anshun, Sichuan province, where they would remain until 1947. They built planks so that the crates would be raised off the ground and air would circulate. And they built sloped, tiled roofs above the storage area to protect from water. The monk was paid for the rental. Guards were stationed to protect the cave. Old Mr. Packer, his wife and three children move into a small three-room house nearby. His wife found a teaching job forty minutes walk away. They had a very basic life, but better than for most during the war.

By April 1938, Japanese aircraft were bombing Changsha. The library where those treasures had been ten weeks earlier, burned to the ground. Had they waited, priceless treasures like the Early Snow on the River scroll, would have been lost forever.

For those of you listening to this as a podcast, you might enjoy the Chinese Revolution YouTube channel. When I add this episode there, it will feature images of the art and you will see the treasures as I tell the story.

As the Japanese approached Nanjing, there were at least 19,500 cases in the new Palace Museum storage vault. The directors inquired about whether the Nanjing Safety Zone could include their facilities. That didn’t seem possible. The Japanese weren’t officially recognizing the Safety Zone and increasing its size might risk all. They would need to move. Han Lih-wu, a Chinese bureaucrat who had helped set up the Nanjing Safety Zone, and who had studied in London and in the USA, was commandeered to the project. He had been managing Britain’s Boxer Indemnity funds as they had been directed towards Chinese infrastructure and education. Now, he got permission from the trustees to provide a short-term loan to get the treasures out of Nanjing. The banks were shut down and no porters would cash a cheque. So, Han went to the customs commissioner and got him to agree to loan him cash. With that, Han secured cash to pay for the ships, the workers and deckhands.

Most of the city, and soon much of the army, tried to leave the capital too. The Palace Museum secured trucks, including one from John Rabe of the Nanjing Safety Zone, although in his diary, he wrote “to take to the harbor, would you believe, 15,000 crates of curios”.

The docks were overrun. Refugees were bargaining and begging to get out of the city. Mounds of war supplies and fresh troops were being offloaded for defence.

In the first few days, 4000 cases of art boarded a steamer heading to Wuhan. This became known as the Central Route.

10 days later, with great urgency, a second ship scheduled to take Palace Museum cargo, arrived in port. This one was a 3000-ton steamer belonging to a British merchant line, named the Whangpu. Other steamers of the same company helped Nanjing to move its post office, its central bank, its records and even shiploads of banknotes upriver.

While the city walls of Nanjing were sandbagged and awaited the Japanese, porters loaded the Whangpu for two days at the beginning of December 1937. They stopped with every air raid siren. The British flagged ship would then pull away from the dock temporarily, only returning once the bombers were gone. The Royal Navy was present, keeping an eye on those Mitsubishi planes.

5250 cases were loaded onto that ship and she was ready to sail. But the crush of refugees on the dockside risked overwhelming the Whangpu and the British captain ordered it back seven or eight feet.

Han Lih-wu had intended to return to the Nanjing Safety Zone and to work there. But the British captain insisted that a Chinese person take responsibility for the cargo. It would not leave without him. A rope was thrown to Han from the boat and he climbed those final feet. Refugees were allowed on the ship and it was completely full. At first, some were holding on to the rails from the outside of the ship, until they could manage to get a foot inside of the deck. John Rabe was sorry to see Han Lih-wu leave. The German who saved so many lives in Nanjing wrote that, Han was “an extraordinarily competent man”.

Ma Heng was in Wuhan. His fourth son, Ma Wenchong, had graduated from a military academy and was a young officer in Shanghai. He was baldly wounded. Battlefield medicine was poor and most soldiers faced days of lying in their own blood before arriving at a hospital. Often wounds festered and infection killed countless soldiers. Malnutrition often worsened their resistance. As luck would have it, or perhaps because of his father’s position, he made it to a hospital in Wuhan. Ma Heng, despite being a good Confucian scholar who put duty ahead of family or feelings, left what he was doing and sat with his son at the hospital. His son was moved. But to a Confucian, to give into spontaneous, emotional acts was undesirable, even unbalanced.

Since shipping was so challenging from Nanjing, the team also moved some crates by rail. That became the Northern Route. The government sent orders to the railways to comply. Hundreds of porters took crates to the train station while others ported to the river. Curators supervising slept in empty freight cars and, when an air raid siren went off, they and the porters jumped below the wagons into whatever filth was down there. Once the bombers passed, they came out and carried on. The cargo on these trains included the Stone Drums of Qin.

Once the wagons were loaded, they were put on a ferry to cross the wide Yangzi River and then connected to a locomotive which pulled them northwest.

Three shipments left by train on the Northern Route before the Japanese soldiers attacked Nanjing.

Not all of the cases mad it. The ferry stopped running on December 3rd and almost 3000 cases were stranded. One more steamer was scheduled to dock, but with air raids and other chaos, never did. The remaining treasures were returned to the Nanjing Palace storage facility. The staff wouldn’t find out what happened to those items until the end of the war.

On December 7th, 1937, Chiang Kai-shek flew out of the capital. The vault at the Nanjing Palace Museum was sealed.

All in all, 16000 cases of treasures from the Palace Museum left Nanjing. Only a few of the most precious took the Southern Route. 7000 took the Northern Route. The remaining 9300 or so took the Central Route.

The Yangzi River, at the heart of the Central Route, was dangerous in war time. Mines floated in the lower section of the river. The Chinese army had removed aids to navigation along the banks. That made dangerous sandbanks and shoals tough to see. The retreating Chinese laid booms to block the Japanese from passing upstream. Japanese planes targeted ships and used the wide river for navigation.

After 400 miles, the Central Route items arrived at fireproof commercial storage facilities of a British company more used to trading in animal hides, carpets and cotton. The sprinkler systems would have been reassuring.

After Nanjing, Wuhan (and specifically Hankou within today’s Wuhan) was for about 10 months, the acting capital of China. The military was headquartered there. Bureaucrats, diplomats, journalists and refugees filled the city. The feel was vibrant and there was a shared sense of purpose: of defending China against Japan.

The government prepared to move even further west to Chongqing in Sichuan. The treasures did too. This time, two British steamship companies helped. One of them was Jardine Matheson, who had made a fortune smuggling opium into China a century earlier. Now it would transport cases a further 350 miles inland to Yichang by steamer and an iron flat-bottomed barge.

Yichang was a key port, just before the gorges hundreds of feet deep that, today, make up the world’s largest hydroelectric facility: Three Gorges Dam. Sun Yat-sen had envisioned a large dam in his work, The International Development of China. The Nationalist Government under Chiang Kai-shek began preliminary work on the Three Gorges Dam in 1939. In 1944, 54 Chinese engineers went to the USA for training for the Yangtze River Project. The Communists later supported it too and it finally was built during the Reform and Opening Up era. The gorges and natural features that make for a good hydro dam, made for poor sailing. There were many boulders. The river was shallow and boiling with white water. The rocks were lethal. Whirlpools sucked vessels in. Vortexes would build without warning. As dangerous as the gorges were, Yichang was not considered safe enough. It was a target for Japanese bombers. So, the priceless cargo had to be shifted to specialized boats able to navigate up through those Yangtze River gorges.

In Yichang, the refugees were in worse shape, having travelled further. The eastern clothes now dirty and threadbare. Many were stuck, no longer having money to buy passage further. Diarrhea and typhoid were common. On the waterfront, families would scrawl messages in chalk. They would state their name and destination, in the hope that anyone they had been separated from would be able to find and follow them.

The steamships that took the cargo to Yichang could not manage the gorges west of the city. Their keels were too deep, and they were underpowered and not maneuverable enough. Traditionally, ships had been hauled upriver here by trackers, who dragged boats upriver using ropes of woven bamboo. By the war, there were specially designed steamships: light, with shallow drafts and powerful engines. They could maneuver quickly, driving hard against the current when travelling up the river and bobbing on the downstream run.

As the steamers were being loaded, Japanese bombers attacked. They devastated the airfield and dropped bombs on the waterfront, causing carnage among the refugees. Luckily, the treasures were unharmed and continued upriver past the chanting trackers, the whirlpools, shoals and reefs and the wrecked ships from earlier times.

Then they made it to Chongqing: China’s real wartime capital. It is a city marked by rivers and rocks. It is crossed by both the Yangzi River and a tributary. The sides of the rivers are steep, with buildings built clinging to cliffs. It is often shrouded in clouds and fog, which would have helped against Japanese bombers. It has winding streets that go up and down hills.

During the war, hundreds of thousands of new residents were attracted to it. The population tripled. Whole universities moved there, as did government officials, diplomats, factories, writers, students and more. It became a mix of people, speeches, and cultures.

One of the warehouses they used had previously held confiscated opium. The Palace Museum staff failed to notice one problem: a rotten joist holding up a part of the floor. Once the weight of hundreds of cases was on it, the joist cracked and the floor gave way. Cases crashed down below. Case 4272 was damaged the worst. It has eight white porcelain wine vessels on three delicate legs. They were probably from the Ming or Qing dynasty. Two of the eight porcelain vessels had shattered. A third lost a leg. The rest had been saved by their careful packing. The outside of six other cases were damaged, but none of their contents were harmed. The warehouse was abandoned. Seven warehouses in Chongqing were used. But everyone knew that Japanese bombers would be coming to the new capital. So, the staff kept looking for better storage facilities.

One plan was to drill tunnels outside of Chongqing. But that would have cost a lot and taken too long, at least a year.

As the treasures were making their way to Chongqing, in early 1938, Japan announced that it would no longer negotiate with China. The Republic of China recalled its ambassador from Tokyo. In March 1938, a former Japanese Foreign Minister rose in its Parliament and said, “The Chinese must be made to realise that they are inferior to the Japanese in culture and aims”.

Soon thereafter, in March 1938, the Japanese fought with the Chinese at Taierzhuang. It is about 300 kilometers, or 200 miles, north of Nanjing. It is on a bank of the Grand Canal of China. Some Chinese troops after the loss of Shanghai had crossed the Yangtze River and were north of it. The Imperial Japanese Army followed them and hoped to rout them, while other troops travelled south from the Japanese controlled territory in north China.

The Japanese had several setbacks after Nanjing and in the lead up to Taierzhuang. The various Nationalist army groups were defending with conviction. The Japanese had the stronger air force and better equipment, but the Chinese were fighting for their lands and showed resolve.

China used some of its remaining fighter planes effectively. Dramatically, the Chinese dug holes in canal banks to shelter from artillery and then emerged and fought hand to hand. It was a cramped town and the Chinese did well with the street fighting. It was infantry against infantry in the rubble. Machine guns, bayonets and hand grenades were all used. The Japanese were accused of using chemical weapons in red canisters, known as red candles. Chinese defenders were brave. Some, from a “dare to die corps” strapped grenades to their chest and leapt under Japanese tanks to blow them up.

Chinese supplies were steady. Ammunition and fuel came. Although, the soldiers complained that they mostly had to eat sweet potatoes. After at least a week of bloody combat, the Japanese gave up and retreated. It was the first Chinese victory of the war. It was a cause for celebration, not just there but throughout China. In Wuhan, there was hope that maybe the Chinese could defeat Japan. Certainly, in this battle, the Japanese did not look invincible.

Japan was making progress elsewhere and the Nationalist Government made a fateful decision. In early June 1938, army engineers blew up part of the Yellow River dike system. This immediately flooded land, mostly already held by the Japanese. It destroyed railway bridges and blocked the Japanese. The KMT initially blamed it on Japanese bombing. The move accomplished the strategic objectives of slowing the Japanese advance, preventing them from advancing into Shaanxi and preserving supply lines from the Soviet Union to China. At that time, after Germany cut off supplies in early 1938 and before Japan attacked the USA, the USSR was the number one supplier of military equipment to China. Since a land route to Chongqing led through Shaanxi, by protecting Shaanxi, it also protected the wartime capital.

But the flooding came at a tremendous cost to Chinese peasants. No warning was given. No one was moved in anticipation. At least 80,000 lives were lost quickly and then hundreds of thousands more through follow-up famine, droughts, and disease. The Nationalist government attempted then to resettle refugees after and did some work to recover land. But it didn’t do enough to help its people. Eventually, those flooded lands became guerrilla bases as ordinary Chinese resisted the Japanese occupiers. I’ll have more to say about guerilla fighting in a future episode.

The Palace Museum staff searched and eventually found a better location near Leshan, about 100 miles west of Chongqing. By water, the trip was three times as long, first along the Yangtze River and then the Min and then along the Dadu, which branches off under a 230 feet high Buddha, carved 1200 years ago. The cases from the Central Route would finally rest in a temple and series of spread-out ancestral halls. Rent was paid and the local community hired and involved.

For much of the year, the Min River levels were too low for transportation. There was a narrow window when the valuables could reach their destination. But because of bombing, they had to leave Chongqing right away. The Yangtze’s levels were higher, so twenty shipments left Chongqing in 15 days for an interim stop at Yibin to await the higher water levels. It cost one of the curators his life. He was on a ship, doing an inspection at night and he missed seeing an open hatch. He fell below to an open cargo hold, suffered head trauma and later died at a Canadian mission hospital. He was buried at the Lion’s Peak, on the south bank of the Yangzi River. He was an only son and his surviving mother was in Anhui. It was only in 1945, that they were able to contact her and provide financial support.

The team managed to get the valuables out of Chongqing before the bombing really began with sunnier weather in May 1939. Bombers came for days in a row. Wooden buildings burned, power was cut and communications with the rest of China interrupted. Thousands of people fled to the riverbanks to escape the fires. At that Canadian mission hospital, where they were trying to help the injured, the floors literally dripped with blood.

Over the next 5 years, Chongqing would be bombed hundreds of times. Before war came to Europe, in the summer of 1939, Chongqing was the most bombed city in the world.

In July 1939, the water levels on the Min River were high enough that the shoals and rapids disappeared under the water. There was a narrow window until mid September when the water level would fall again. The first shipment of 350 cases went fine. But the second ran into an underwater shoal thirty miles into its journey. The ship’s engine was damaged, and water started to enter the cargo hold. The pilot turned the ship around and returned to Yibin. When it passed a ship heading upriver, that one decided to turn around too. The pilots then announced that the journey was too dangerous and refused to travel up the Min. There was only 8 weeks left in the high-water season and the pilots were on strike.

It turned out that the reason the ships weren’t moving was that the Palace Museum had contracted with a transportation company that owned no steamships. It had subcontracted with those who had steamships and kept a significant share of the revenue. Now the steamship owners were renegotiating. Mr. Liu, on behalf of the Museum, made no progress. So, Ma Heng sent in Na Chih-liang. He had been 17-year-old when they started the first inventory at the Forbidden Palace over 15 years earlier, putting the ink brush in his mouth to warm it up. Now he had to get the fragile cargo moving again while the water was high enough. That left 4 weeks. Air raid sirens were going off regularly.

Na considered what power he had. Soldiers were guarding the crates. They were effectively under his command. He told the transportation companies that if they did not get moving, his soldiers would commandeer their steamships. That worked.

All the crates then reached the base of a 230-foot-high Buddha and had to be transferred to low sided, shallow-draft wooden boats. The last river trip was 9 miles of shallow water, filled with sandbars and other hazards. Na had engineers dynamite rocks to make navigation easier. He hired porters to transfer the cargo from the steamers to the new wooden boats. It meant carrying crates under shoulder poles half a mile each way across muddy paths. The road was still under construction.

Then, trackers on land pulled the boats forward using ropes of braided bamboo. Steersmen worked to keep the boats off the shoals.

At one point, the ropes pulling one of the boats unraveled and then snapped. A curator, Liang Tingwei, was onboard and began screaming. The boat picked up speed as it moved downstream. It was pitching and spinning as it descended to the bigger Min River. At the last bend, the steersman took a chance and rammed the tiller hard to the right, as far as it would go. The boat lurched and inched its way toward the bank. Its keel ground into the sandy bottom. They were aground and safe.

On August 19th, 1939, Japanese bombers targeted Leshan, the community by the 230-foot-high Buddha. It had only 60,000 people. Nowhere seemed safe from those planes. A third of Leshan burned and about 1000 lives were lost. Luckily the crates had left before then. The committee worked hard to be one step ahead of the bombs.

By September 19th, 1939, all the crates of the Central Route were in their resting place. They were stacked in the cool, dry, dark halls of Angu. Shelves helped keep them off the ground, with air circulating around them. Coatings were put on the wood to prevent attack from termites or other insects.

The Northern Route

After leaving Nanjing, the train taking 7000 cases of objects travelled north to Xuzhou, the same city where they had worried about bandits about 5 years earlier. Then the trains headed west to Xi’an. The military authorities there, originally from the east coast, were cooperative. It was decided that the cargo would carry on to the end of the line at Baoji, to the west of Xi’an. It is roughly north of Chongqing. The railway had only recently been extended to that city. It didn’t feel safe, since the Japanese were focusing on railway infrastructure. As quickly as they could, the treasures were loaded onto trucks to head even further inland.

Not everything went smoothly. One truck was loaded from the train and pulled away, only to ignore a railway crossing. A train smashed into it. I believe the driver was ok, but two cases were severely damaged. Imperial yellow porcelain bowls were shattered. Domed glass covers for clocks were also broken. It was a momentary lack of attention.

The items were placed in temporary storage. Na Chih-liang returned to Wuhan, only to be ordered back to Baoji, along with 8 family members of curators. The trip back west was chaotic. The crush of people boarding the train was tremendous. Many people without tickets had to stand for the whole 300-mile journey. Na and his group had tickets and he had to get others to stand up so that they could sit on their reserved seats. He then felt guilty for being hard on these penniless refugees.

One of his tasks in Baoji was to do an updated inventory. The crates had left Nanjing in such a rushed manner that it wasn’t yet clear which items had ended up where. He realized the crates were stacked too close together. They could barely be moved. He began searching for an even better home for them. They, including the Stone Drums of Qin, would travel south by truck. On a map, the destination was only 90 miles away. But there was the Qinling mountain ridge in between and this was winter. The trucks would have to climb up and over a high mountain ridge on corkscrew roads with hairpin turns beside precipitous drops to the valley below. Having driven on such a road once in my life on a snowy day in central British Columbia, I can say that the very idea makes my palms sweat. And I’m sure those 1930 rural Chinese roads were even more dangerous than the ones I experienced and never want to repeat.

With 20 cases per truck and 7000 crates to move, it would take over 300 journeys. The chance of them all going well seemed slim, but there was little alternative. The military agreed to supply the trucks. A plan was developed. But already on the fourth shipment, there was a problem. Fresh snow was falling. As the trucks climbed, the snow became heavier. When they stopped in a village for food, they were told a landslide ahead made the road impassable for all but the smallest vehicles. The military drivers stayed put. But the weather worsened, and they could not even go back. They had not brought provisions, as they had planned to return without sleeping. The little noodle shop in the village ran out of food. The soldiers might be stuck without proper clothing and without food for days.

Luckily a vehicle came from the other direction. They flagged it down and asked the driver to relay a message to Curator Na in Baoji. Na then organized supplies to be taken to the stranded drivers. He wanted to go along, but his team refused. They couldn’t have the most senior team member go off the road to his death. A more junior team member and an army officer volunteered instead. But no driver was so selfless. None volunteered. Bonuses and cajoling didn’t work. Finally, one young man stepped forward and agreed to drive. Bundled in padded jackets and scarves, they headed out. They inched up the mountain in whiteout conditions. It was tough to see the road. They looked for signs of previous tire tracks. The truck skid and slid. The officer leaned out the window trying to get a better view and to avoid them falling to the river below. They made it and laborers eventually cleared the landslide and the weather improved. The shipments continued, but never again without snow chains for the tires. It took 48 days to get all the cases over the Qinling mountains.

They made it to Hanzhong by April 1938, but its airfield had already been bombed twice. Trucks began moving crates south into Sichuan province. While some were moving and others waiting for transportation, one of the soldier guards decided to play with his grenade. It fell to the ground and exploded. He was killed and two of his comrades injured. A porcelain bowl from the reign of the Qianlong Emperor was smashed and another porcelain jar lost its neck. No one knew why the guard was handling a primed grenade.

The plan was to travel to Chengdu, 350 miles away along poor, twisting mountain roads. The logistics were challenging. Trucks were hard to find. When they did find some, the drivers were paid by the day, rather than the journey, and found every reason to stop, pleading mechanical problems.

Na rode along a few times and found the views spectacular. He watched trucks spiral up the mountain, along switchbacks. Na felt that the whole mountain was filled with vehicles.

Na passed the so-called Thousand Buddha Cliff. A cliff face forty feet high was home to thousands of tiny chambers, each with a Buddha inside, carved in stone. Among these holy statues, are also one of a Tang Dynasty princess. As a museum curator, he felt both blessed to be seeing such historic sites and saddened to be passing them quickly on official business. Ma Heng once travelled there too and wrote a poem mentioning these winding, mountain roads.

Once they reached Sichuan, the bridges were out. The trucks had to cross rivers by wooden ferries. Those were propelled by boatmen using long bamboo poles. It took hours for muscle power to get heavy trucks across a river.

They made it to Chengdu and were carefully inspected by auditors and finally moved to the final stop of the Northern Route: Emei. It was a small town without electricity or running water at the base of a sacred mountain. There were two temples there and the team hoped that it would not attract Japanese attention. The team would have preferred staying in Chengdu, with its spicy food and restaurants with interesting names like “Don’t Come If You’re Busy” and “No Going Home Unless Drunk Café”.

Often the storage facilities they had used were bombed shortly after the treasures had moved on. Other times, staff barely escaped bombing runs with their lives, but they did live. Na Chih-liang later wrote and wondered if they were protected somehow. “They were bombed without being hit and dropped without being shattered. How was this real?” Na lived for 7 years in that small community.

I would like to share more about the final journey of the treasures after the war, first to Nanjing and then some on to Taipei as the Nationalists retreated and the rest on to Beijing to finally be returned to the Forbidden City. Since 2022, there is even a branch of the Palace Museum in Hong Kong. But I feel this post is already quite long. When we get to the end of the Chinese Civil War, hopefully we can return to this topic and find out who from the Palace Museum staff moved to Taiwan and who stayed in Beijing and the consequences of those decisions. What you can know is that the treasures of the Palace Museum were safe in their hiding spots in and around Sichuan. Three storage facilities, each at the end of the southern, central and northern routes, all were safe and secure. The priceless artifacts did survive the war, thanks to the momentous efforts of the Palace Museum Board of Directors and staff. Not all the Chinese who tried to flee the Japanese were so fortunate.

P.S. Did you know that The Chinese Revolution is on YouTube and is also a podcast?

Great piece! Thank you Paul. I will look forward to the continuation, how the treasures reached Formosa after the revolution, and how the pieces were selected at that time. I can see the picture you selected is the National Palace Museum in Taipei - which I have visited, also at nighttime with the dramatic illumination. Every item, especially the high level of craftmanship in creating them, is very impressive and well displayed. I assume that the original Palace Museum in Beijing convey the original architecture better, but is their collection different and is it well preserved?

This museum saved many Chinese historical treasures from loss and destruction in so many ways. My Chinese friends also realized that much was saved from the Cultural Revolution because they were in Taiwan. My Taiwanese friends said that someday they will return to the mainland. Who knows! But they are in a place where they can be viewed and enjoyed by all. Wonderful!