After the Huizhou uprising debacle in late 1900, Sun Yat-sen laid low for about two years. This was a low point for Sun, while Kang Youwei’s Society to Protect the Emperor was approaching its peak in North America.

Then from 1903 to 1905, Sun Yat-sen travelled. He lived in Hanoi, then Hawaii, then Europe before returning to Japan in 1905.

The Chinese students abroad, in Japan and in Europe, for the most part, did not respect him and considered him an uncultured outlaw. Some Chinese students in Paris even reported him to the Chinese legation there.

Japan was now less interested in fomenting revolution in China. They were aligned with the Qing Court since it was pursuing modernizations and reforms after the Boxer Rebellion. Plus, Japan was more interested in Manchuria and north China, which was far from Sun’s native south China.

At this particular moment, France was perhaps interested in backing Sun. France had a strong presence beside south China in French Indochina. It aspired for more influence and profit in south China. French colonial officials in Hanoi seemed open to supporting Sun, while gaining opportunities for railroads and mines for the French.

Sun had begun discussions with the French before the 1900 uprising. Then because of internal French politics, talks were on hold until the fall of 1902 when Sun was invited to Hanoi by the governor general for a colonial exhibition.

For six months, Sun resided in Tonkin, building contacts. But at this point, internal French politics still did not favour intervention in China.

In February 1905, Sun arrived in Paris and had numerous meetings. Some notes were kept in the Quai D’Orsay archives, recorded by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The French created the Intelligence Service on China in May 1905 as a result. They wanted more information, which Sun would provide them. Over the next year, he organized some intelligence missions for them. Sun asked his men to guide them. As a result, the Service’s reports were pretty favourable to Sun. But the French Minister in Beijing refused the reports. He considered Sun an amateur or adventurer. Then the Qing court in Beijing learned about the activities and complained. The Service was shut down.

Sun returned to Yokohama, where he learned that most of his supporters were now following Liang Qichao and the reformers. He set off for Hawaii and found that his letter of introduction for Liang had done the same and that the reformers had gained huge support among the Chinese in Hawaii, including with Sun’s own brother. Sun Mei was local President of the Society to Protect the Emperor!

Liang had even joined some Triads, which Sun had not done.

Sun took to the offence with the Chinese overseas. He started with Chinese Christians. Sun, of course, had converted and been baptised, while Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao had not.

In 1903, Sun Yat-sen returned to Hawaii for the first time in 7 years. Chinese Pastors invited him to speak and Sun turned out to be a forceful orator. He acquired a newspaper and took aim at the reformers. He made a clear contrast between the two movements. He accused Liang of having two ways of talking. Of protecting the emperor and carrying out revolution. Those were separate things. You can’t have it both ways. Sun started to regain followers, including his brother.

Next, Sun joined the Triads in Hawaii and got letters of introduction for their branches on the continent. Instead of hiring their members, Sun began to infiltrate them. He set up new Triad charters, which closely matched the goals of the Revive China Society.

He didn’t have much success yet. But now he had four newspapers going, one in Hong Kong, Hawaii, San Francisco and Singapore. He was deepening connections with Triads and Chinese Christians. And his visibility was increasing again, even if the Society to Protect the Emperor was still more popular.

In 1905, Sun took another step towards building an anti-Manchu revolution with the founding of the Revolutionary Alliance.

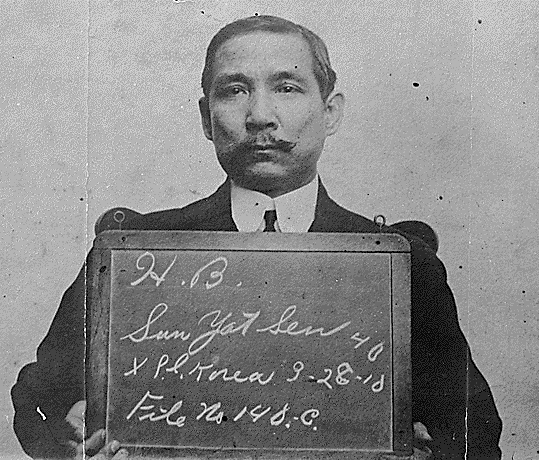

Many Chinese students abroad wanted radical reforms or revolutions. Those that wanted revolution were willing to work under Sun’s leadership, given his age and experience. He was approaching 40 years old, twice the age of many of the students. He also had been involved in revolutionary activities the longest. Miyazaki Torazo’s, The Thirty-three Years’ Dream had been translated from Japanese to Chinese and described Sun favourably. These factors were enough to overcome what the students considered to be his meagre education and questionable tactics. This was revolutionary in itself: Chinese intellectuals choosing to follow a peasant’s son.

Chapters of the Revolutionary Alliance were founded in Tokyo and in Europe. It was there, organizing, that Sun was reported to the Qing authorities by Chinese students.

The Revolutionary Alliance was to have 5 regional offices in China and be a national organization. Sun used it to articulate the ideas that would be at the core of his agenda for the rest of his life. The overthrow of the Manchus, the restoration of China, the adoption of a republican regime and the people’s livelihood. Sun was beginning to articulate the People’s Three Principles.

I’ll have more to say about those principles later. Sun himself would continue to refine them for the rest of his life.

The Revolutionary Alliance was far more intellectual than Sun’s earlier endeavours. Of the almost 1000 members in 1906, all but 100 of them were intellectuals. Despite their academic bent, those students were more focused on the anti-Manchu and nationalist aspects. It was Sun who brought the ideas of republicanism and the people’s livelihood to the organization.

The Alliance was a federation. Individuals did not join directly. Regional groups joined the Alliance and individuals were part of their regional groups. The Guangdong group was closest to Sun. It included many students. There were also groups in Hunan and Hubei, with their own leaders and they had the most members. One of its young and active members was Song Jiaoren who in the new Republic of China will help make the KMT the most successful political party. Leaders from Zhejiang-Anhui joined in 1906.

The Qing Court took steps towards establishing a constitution and legislative assembly as of 1905, starting with local assemblies in the provinces. This cut into the case to support the reformers, as reforms were already happening without them. The Revolutionary Alliance was pushing for something entirely different, government of China by Chinese and not by Manchus. That resonated with the Han majority, who make up about 95% of the Chinese population.

Sun believed in a republic because he considered it the most advanced form of government. He saw no reason to push for a constitutional monarchy, or second best, when China could have the most modern government system.

Interestingly, that argument could ultimately make communism an even more attractive proposition. Because communist government became the absolute newest form of government. When combined with anti-imperialism, which appealed to Chinese humiliated by foreign imperialists, that became a strong combination. But that is for another day.

At this point, a Chinese republic was Sun’s goal.

In 1907 and 1908, Sun supported uprisings in Guangdong and Guangxi, in southern China. They involved secret societies, much like Sun’s previous efforts. Sun was not directly involved in them.

In September 1907, he did get involved in an uprising in western Guangdong, close to the border with Guangxi and with French Indochina. Sugar planters had been protesting for months because of a new tax. Also, two local military leaders had joined the Revolutionary Alliance and had been kicked out of China’s New Army in Jiangsu because of spreading revolutionary ideas. Now they were in the New Army in Guangdong.

Sun sent emissaries to liaise with those officers and French instructors trained the rebels. But the officers never cooperated and the effort fizzled. Those officers then helped troops sent from Guangzhou restore order. It seems they preferred to side with whoever paid them more.

Three months later, in December 1907, a rebellion broke out at the pass between China and Vietnam which is called suppressing the Vietnamese in Chinese: Zhennanguan. This one was more sophisticated, taking place along two major railway lines from Tonkin into China. Many of the rebels were Chinese working for the Compagnie de Chemin de Fer de Yunnan, a French railway enterprise. Once the rebels took Zhennanguan, Sun himself took the train in Vietnam with some fellow revolutionaries and at least one French army captain on leave. When they reached a Chinese fort that they expected would be loaded with weapons, it was mostly empty except for one Krupp cannon. They used that to bombard the imperial troops, but Sun returned to Vietnam to negotiate for more weapons. A bank was willing to make a loan if a key administrative centre was captured. It wasn’t and the regular Chinese troops put the rebels down.

Huang Xing, one of Sun’s lieutenants tried again in April 1908 along that same French rail line. The rail company hoped to win the right to extend its line into a more promising area of Yunnan province. This time, regular Chinese troops joined the rebels. There were several thousand involved in the uprising. But the use of mercenaries had its downside. They insisted on being paid before moving. Huang went to Vietnam to seek funds to pay them. But Qing pressure on France, and internal French politics led him to be arrested and expelled from Indochina. Without the funds, the insurrection was doomed and the Revolutionary Alliance’s work with France ended too.

Sun was criticized for these failures by the leadership of the Revolutionary Alliance along the Yangzi River.

What Sun mostly did during the 1907 to 1911 period was fundraise for revolution. He travelled the world and raised funds. His costs were covered by the fundraising, but he seems to have lived simply and have been a true believer. While the money flowed to purchase weapons and buy converts (like secret society members and military officials), he does not appear to have been corrupt.

The fundraising really increased as 1911’s revolution approached. That year, Sun raised US $35,000 in Canada alone. That would be worth millions of today’s dollars.

In January 1911, a plan was made for an uprising organized from Hong Kong to take place in Guangzhou. Instead of secret society members, this time overseas Chinese who believed in revolution would be the vanguard. Weapons were purchased in Japan, Indochina and Siam (now Thailand). Forty secret cells, operating in isolation, spread the weapons. An Alliance funded newspaper spread propaganda and in particular, targeted soldiers in the New Army. Spaces were rented by fake couples supposedly planning their weddings. Weapons were hidden in curtained sedan chairs supposedly carrying the brides to be.

Emissaries were sent to the Yangzi River, to alert their comrades to be ready to act in their region too.

But a Chinese man from Malaysia assassinated a Manchu general on April 8, 1911 and the officials were on high alert. They brought in new troops. Sun’s lieutenant Huang Xing was uncertain what to do. Ultimately, he launched an uprising on April 27. They captured government offices, but then loyal soldiers recaptured them. When rebels arrived from Hong Kong, the rebellion had already been crushed.

The authorities executed between 72 and 86 revolutionaries, depending on the source.

October 10, 1911 (often called Double Ten) was the start of the Wuchang uprising that ended the Qing Dynasty. Wuchang is the oldest of the three cities that now make up Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province. It’s an important city in the Yangzi River valley. It was loosely connected to the Revolutionary Alliance, but not at all directed by Sun. The two main instigators in Wuchang were former students from Japan and officers and men of the New Army stationed in Wuchang.

I’ll discuss the New Army more in a separate episode when the New Army and General Yuan Shikai are discussed at length.

While Song Jiaoren was organizing in the area for the Revolutionary Alliance, he can’t really take credit for the insurrection. It was the rebellion by the Wuchang garrison that was important. In a single night, they took control. They needed a leader and imposed it on a garrison officer, Li Yuanhong, who assumed the military governorship of Hubei province. So started the first revolutionary government in China!

The next day, the New Army soldiers sought and received support from the local gentry. These local leaders were happy to run with this opportunity to take more control of government than allowed by the Qing. Merchants supplied loans and with the military, gentry and merchant classes on board, a stable revolutionary government had been created. There already was a provincial assembly created by the late Qing reforms and its president became civil governor along with Li Yuanhong as military governor.

Song Jiaoren moved to the southern Yangzi to build on Wuchang’s success and hoped to replicate it. In Shanghai, the Revolutionary Alliance was the dominant force and they attacked and gained control of the Jiangnan arsenal and then the city. They also gained the support of the local elites, which in Shanghai included a lot of merchants and entrepreneurs, as well as administrators, and they caused the governors to proclaim Jiangsu and Zhejiang independent of the Qing.

By early November 1911, 14 provinces had seceded. The end of the Qing Dynasty reminds me of the quote by Ernest Hemingway about becoming bankrupt. It happened “gradually and then suddenly.”

The issue of setting up a new national government was pressing. Nanjing was selected, in part because Beijing was still under Qing control. The Wuchang and the Shanghai groups each had their own ideas for a provisional head of government. There was no agreement.

Sun Yat-sen was overseas. He had been fundraising in the United States in early October 1911. When he learned of the uprising in Wuchang, he did not rush back to China. Instead, he rushed to New York and London. He pressed the International Banking Consortium, through an intermediary, to ensure that funds for the Manchu dynasty should be redirected to the republican government instead. The bankers weren’t sure what would happen and hedged their bets by not advancing funds to either administration.

Sun was able to get his banishment from the British colonies lifted. He was then able to return to China via Singapore and Hong Kong. He travelled to Paris and got a similar commitment from the bankers and government there. There would be no more support for the Qing. But none for the revolutionary government...yet.

Sun returned to China in December 1911. He used the lifting of his banishment to make a big entrance in Hong Kong. He was warmly greeted by his revolutionary allies and also by Cantonese merchants. Hu Hanmin, one of the Revolutionary Alliance members, was now military governor of Guangdong after its secession from Qing China.

Hu tried to convince Sun not to go to Nanjing. Instead, he wanted him to stay in Guangdong and set up a provisional government in the south in opposition to forces like Yuan Shikai in the north. Hu thought that any provisional government in Nanjing would be fatally compromised and that a strong south would be key to a successful and lasting revolution.

Sun concurred with Hu’s analysis but thought that ridding China of the Manchus was the most important immediate revolutionary objective. He didn’t trust Yuan Shikai either, but believed he needed to go to Nanjing. Hu relented and they both travelled to the new revolutionary capital together.

They arrived in Shanghai on Christmas Day 1911. Sun’s arrival provided a solution to the impasse about leadership. Sun would be the first President of the Provisional Government. He was elected 16 votes to 1 by the Parliament. On January 1, 1912, he began his Presidency and Year 1 of the Republic of China.

He took his oath of office at the tombs of the Ming emperors, in the countryside close to Nanjing. He was not pompous and visitors described him as serious and thoughtful. He did allow himself use of an automobile for his duties. His able revolutionary lieutenant, Huang Xing, was Minister of War and effectively Prime Minster. That was quite the rise from student in Japan and organizer in the Revolutionary Alliance. The first cabinet was full of remarkable people, including the Foreign Affairs Minister who spoke at least 5 languages and who had translated the German Civil Code. The Industry Minister had successfully developed the textile industry in Shanghai. Wu Tingfang, who had been reforming the Qing penal code, transferred over to the republic as Minister for Justice. Unfortunately, this was not Lincoln’s Team of Rivals. Instead, their internal bickering made them mostly adversaries. There were immediate tensions between the cabinet and Sun who was trying to honour promises made to soldiers and backers of the revolution. He wasn’t receiving the funds he needed and cabinet didn’t like his independent streak.

The main issue during his brief 45-day Presidency was dealing with the Manchu regime. Yuan Shikai, who will be discussed next episode, controlled the Qing Army and with it, the fate of so many things. Negotiations led to the abdication of the baby emperor and General Yuan’s agreement to come over to the revolution, in exchange for Sun agreeing to turn over the Presidency to General Yuan. I’ll have more to say about General Yuan and the transition in a future episode. But for now, it is worth highlighting that Sun was willing to give up the Presidency for a united China. The union of north and south China was worth giving the Presidency to General Yuan. Sun hoped that China had its George Washington.

Unfortunately, Yuan Shikai was not General Washington. The early Republic would be troubled. Sun Yat-sen’s story was not over yet. Not at all.

Sun Yat-sen has gone from peasant’s son to prodigal son, to doctor, to revolutionary, to kidnap victim, to hero, to fundraiser and organizer and to the Presidency of the Republic of China and now was taking a step back for what he believed was the greater good for China.