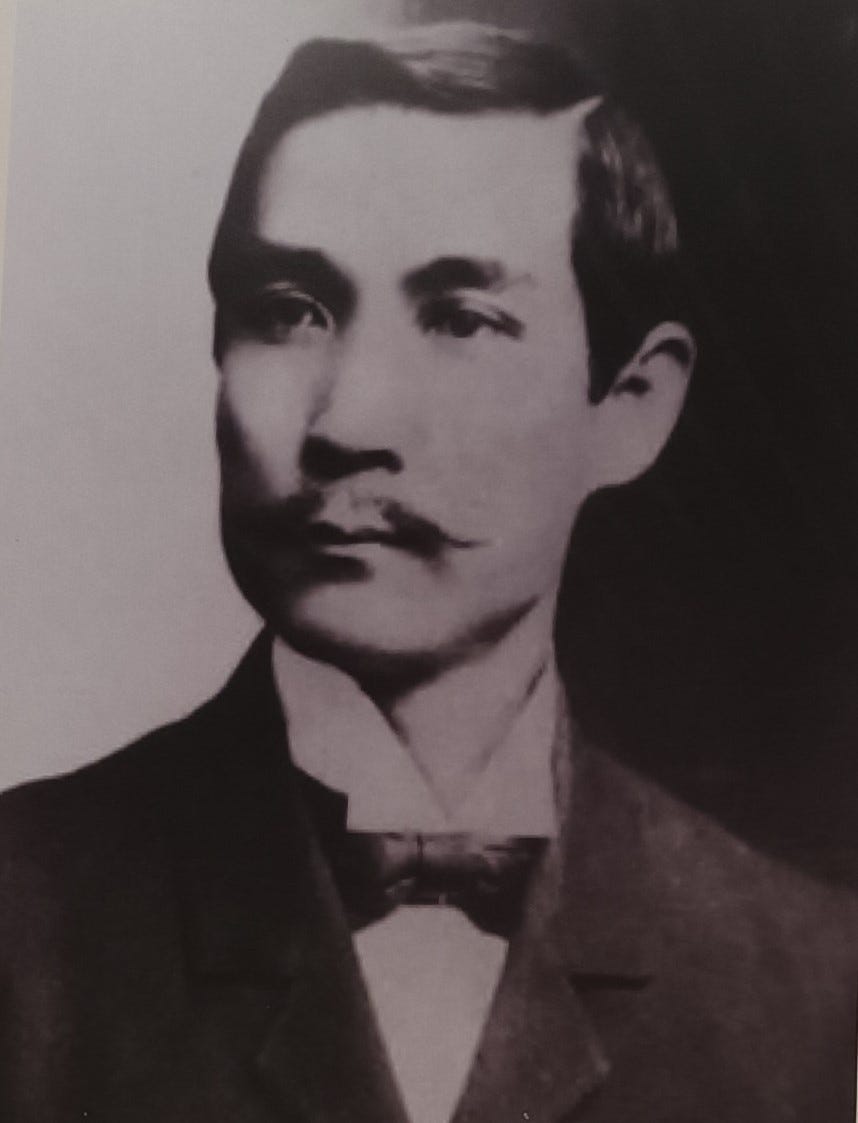

Dr. Sun Yatsen, Revolutionary, Part 2

His Revolutionary Journey Continues and Experiences Setbacks

In August 1897, after 8 months in London, Sun settled in Japan, where he would live for the 3 years. He took on a Japanese name, Dr. Nakayama.

Some Japanese saw in Sun, with his celebrity status following his kidnapping in London, a hero capable of regenerating China.

This is Part 2 of the look at Sun Yat-sen, the Chinese revolutionary who would come to be the first President of the Republic of China.

When Sun arrived, Okuma Shigenobu was Japanese Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs. He thought Japan having modernized first, had a moral obligation to protect China against Western aggression and help it to reform. It owed a cultural debt to China. If only a “hero” would arise, patriotism would be revived and China would be restored to its place among the great powers.

This is not the place to discuss all of the different current of thoughts and ambitions among the various Japanese players. The point simply is that there were a variety of Japanese personalities, ways of thinking and approaches with respect to China and the Chinese. At least some of them could be interpreted positively by Chinese wanting to modernize and restore their country.

One Japanese man who worked closely with Sun was Miyazaki Torazo. He was four years younger than Sun and had been educated in a private, liberal school where he had learned about the English and French revolutions. He too had converted to Christianity and learned English. He later abandoned Christianity and sought adventure in southeast Asia and China. Through an intermediary, he received funds from the Foreign Affairs Ministry to find and cultivate a Chinese hero. He received a copy of Kidnapped in London and learned that Sun would be travelling to Yokohama.

They met and they hit it off. Even though Miyazaki’s English was limited and Sun spoke no Japanese, they were able to communicate in writing. Written Chinese characters were clear enough to each other to communicate their meaning. Chinese characters are one of the written languages of Japanese, also known as Kanji in Japanese. By writing the characters down, each was able to read, understand and write with the other, even though they did not speak the same language.

Sun tended to say what his audience wanted to hear. In this case, he said that he wanted help the four hundred million Chinese wipe out the insults heaped on the yellow peoples of Asia and restore the way of humanity. Miyazaki liked Sun and believed he had found his Chinese hero. Miyazaki introduced him to other Japanese.

At the end of 1898, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao also moved to Japan following the end of the Hundred Days of Reform and their flight from China was described in the posts about the Empress Dowager.

Sun never became close with Kang Youwei. They tended to always be competitors for the attention and support of the Chinese outside of China. But the relationship between Liang Qichao, who was younger than Kang, and Sun was more nuanced.

Kang Youwei was received warmly in Japan, including by Okuma Shigenobu the Japanese Prime Minister. Yang was treated almost as like government in exile and greeted by higher ranking Japanese than Sun. Both Yang and Sun received Japanese funding and they were encouraged to work together. Kang refused and considered Sun to be an uneducated bandit. Kang thought that Sun’s promotion of his kidnapping in London was humiliating to China.

Within a year, Kang had overstayed his welcome in Japan. That was partly because of pressure put on Japan by the court in Beijing. But also, because Kang was haughty, unaccommodating and elitist, which rubbed some Japanese the wrong way.

Kang left Japan for Canada, where he was destined to co-found the Society to Protect the Emperor which was discussed in the post about Kang Youwei.

Liang Qichao stayed in Japan and was able to emerge from Kang’s shadow. He exchanged ideas with Sun and negotiated to bring the two opposition groups together.

Liang created a school for further education in Tokyo in 1899 and attracted not only former students of Kang from China, but also Chinese in Yokohama. Sun provided funding and it had the Confucian sounding name: School of Great Harmony.

Liang was getting closer to Sun by publishing increasingly anti-Manchu articles in his newspaper in Japan. Some articles were co-signed by both Sun and Liang.

Kang may have been worried about losing his influence on Liang and invited him to travel to Hawaii and the United States on behalf of the Society to Protect the Emperor. Because Liang and Sun were close at this time, Liang obtained a letter of introduction from Sun to his brother in Honolulu. Liang then strengthened his bonds with Kang again in North America.

The letter of introduction helped Liang gain support for the Society to Protect the Emperor in Hawaii. This let Sun Yat-sen down. As it helped the reform party gain support over Sun’s revolutionary efforts, with Sun’s close family and friends.

Kang’s Society to Protect the Emperor would do better than Sun at raising money among the Chinese overseas for years. But Sun had an advantage at this moment. Japan believed in this hero and was supplying him with funds. Kang did not have that.

Sun’s revolutionary nationalism wasn’t limited to China. He also supported it for the Philippines, which had been a Spanish colony for centuries. With the Spanish-American war, changes were coming. Philippine nationalists didn’t want to be controlled by the United States. They wanted Philippine independence. The United States seemed open when it was independence from Spain. But once the USA had its own designs on the Philippines, they opposed independence and preferred American control over the islands.

Emelio Aguinaldo, an anti-American Filipino guerrilla asked Miyakazi for help in Hong Kong and reached out to Sun. Sun responded warmly and Japan offered to help via Sun. Aguinaldo could use Sun to purchase and transport Japanese weapons. Those weapons left Shanghai by boat in June 1899, but there was a storm and they were sunk at sea.

Sun now also re-activated activities in Hong Kong. The main leaders of his Revive China Society had fled Hong Kong after the failed insurrection in 1895. He was still in contact with Yang Quyun, who had joined him in Tokyo. And some activities had continued and there had been some indirect contact between them and Sun through Miyakazi.

In 1899, a new Chinese language newspaper was launched in Hong Kong: the Chinese Daily. Its main audience was in Guangzhou. Sun wanted a publicity arm for his revolutionary activities. It was initially funded by Japan and had the support of Ho Kai, who had publicized Sun before. Chen Shaobai was entrusted with its management. To its credit, it published until 1913...quite an achievement for an opposition newspaper at that time and place.

British authorities in Hong Kong were open to oppositional newspapers then because it coincided with the Boxer Rebellion and conflicts between Britain and the Qing court.

Sun also made efforts to remobilize the secret societies. Zheng Shiliang, Sun’s old friend, again helped as a go between with the secret societies and Triads. Chen Shaobai, publisher of the newspaper, was given the title White Fan, a military advisor to the Triads of Hong Kong.

This time, Sun did not limit himself to Guangdong and Guangxi. He also made contacts with the Society of Elder Brothers of the Yangzi River valley. This was partly through the Japanese and partly through a Hunan reformer that Sun had met in Tokyo.

It is worth mentioning that the Chinese in China did not all speak the same language. Mandarin Chinese was spoken around Beijing. Cantonese was spoken in Guangdong province and in Hong Kong. That has not really changed much today, although Mandarin has taken on more importance in the south as strong central government and Chinese Communist Party supported education and media penetrate. Mandarin is the only official language in the People’s Republic.

What is perhaps less appreciated is how much more common Wu Chinese was around the Yangzi River and Shanghai at this time. Around 1900, Wu Chinese was the 9th most spoken language in the world. Mandarin was 1st. Wu Chinese is sometimes called Shanghainese, but that is not accurate. The language went beyond Shanghai and there was northern Wu and southern Wu. After the Chinese Communist Party came to power, use of Wu was curtailed and Mandarin encouraged. And as mentioned in the episode about Chinese overseas, many Chinese people’s first language was Hokkien or Hakka. There were a lot of different Chinese languages being spoken at this time and perhaps only 1% of the population was literate and able to read Chinese characters. Coordinating people across regions and language groups was more work than we might think.

For the first time, Sun had the support of a young revolutionary from a high-ranking family. Shi Jianru’s grandfather had completed the highest examination degrees and the family was wealthy. This was a bad omen for the Qing. High ranking families were beginning to organize against the imperial regime. That would be a crucial factor come 1911. In this case, he had begun reading the Classics. But at aged 19, had attended the Canton Christian College. This young revolutionary was first introduced to the Society for Common Culture of East Asia and then through that Japanese funded organization to the Revive China Society.

The Revive China Society brought the Triads and the Society of Elder Brothers together for the first time in 1899 in Hong Kong. Now Cantonese speaking secret societies were meeting with Yangzi River equivalents. They agreed to ally under the authority of Sun Yat-sen. It was called the Association for the Rebirth of the Han. Wine and pigeon’s blood flowed.

But that alliance of convenience broke down. A key contact left the Society and joined a Buddhist monastery.

And with the Boxer Rebellion, many high officials in southern China disassociated themselves with the Qing court. They wanted to prevent unrest at home or retaliation from imperial powers.

Liu Xuexun, the owner of the imperial examination betting ring, who supported Sun and hoped to found his own imperial dynasty, approached Earl Li Hongzhang about separating the south from the north. Robert Blake, the British governor of Hong Kong, was in favour and advocated an alliance between Earl Li and Sun Yat-sen.

Ultimately, Earl Li did not agree and travelled north instead.

Huizhou was selected as the site of the uprising Sun was planning. Zheng Shiliang’s family was from this area. He was one of Sun’s 4 bandits from college. He was the one connected with the Triads. The plan was for the rebels to assemble in small towns, move on Huizhou, a prefecture level community in eastern Guangdong, take control of it and then move on Guangzhou, the provincial capital. 23 Triad leaders were members of the Revive China Society at this time. The secret societies were to be the main armed forces of the insurrection.

In Guangzhou, Chinese Christians were heavily involved in the preparations to take that city, including the Christian bookseller who had been involved in 1895. Now too was Shi Jianru, the gentry family son who had attended the Canton Christian College.

But Sun got distracted seeking funds and weapons for the uprising. Japan controlled Taiwan since 1895 and with the Boxer Rebellion underway, Japan was interested in gaining control or influence over Xiamen, on the Fujian coast on the mainland beside the Taiwan Straight. They wanted to work through an intermediary and the Japanese Governor of Taiwan offered Sun support if he would seize Xiamen. Sun visited the Governor in Taiwan and decided to seize Xiamen rather than Huizhou.

This was short sighted. Sun’s teams contacts were strongest in Guangdong and not in Fujian province. Also, it required longer distances for the secret society rebels to travel from their hometowns to Xiamen, rather than nearby Huizhou. And Sun had no real contacts in Xiamen.

The uprising started normally. Zheng’s men gathered, spread rapidly and routed the first government troops they met in Guangdong. They were then about 20 kilometers south of Huizhou. They received warm welcomes from local inhabitants and were well disciplined. They did not harass any Chinese Christians. Now they needed to link up with allies in Huizhou and then march together on Guangzhou, to meet up with others.

Instead, at this point, Sun’s new orders came. Instead of 20 kilometers to Huizhou and then perhaps 75 kilometers to Guangzhou, they now were ordered to travel about 500 kilometers through unfamiliar territory into another province, where they had no local contacts. They were harassed by government troops and were exhausted. Finally, they received word that the Japanese had backed away from the plan and would not support them. This major detour had been useless. The rebels that were left, returned home.

In Guangzhou, Shi Jianru, the young gentry family revolutionary, organized a bomb attack on the provincial governor. It missed its target. He was arrested in the police repression that followed. He was beheaded.

Others were never arrested, but may have been killed nevertheless. Yang Quyun was struck down in his own classroom. And Zheng Shiliang died after a meal. It was reported as a heart attack, but those close to him believed it was poison.

Sun Yat-sen returned to Japan with nothing to show for the efforts. Japan had let him down, as he had let down his troops and supporters.

If Sun’s life had ended there, we would certainly not be talking about him today. Next time, we’ll see how he picked himself back up and ended up elected as the first President of the Republic of China.