In the 19th century, when Chinese men went abroad, it was usually with the idea of earning a fortune and then returning home. If they travelled with a family member, it was often a brother or cousin. Men were far more common in the overseas Chinatowns than women.

In 1870, it was estimated that 7 out of 10 women in San Francisco’s Chinatown were prostitutes. It was a difficult life that often had no real escape. In 1876, one such escapee, known to some as Yellow Doll, was found hacked to pieces.

Sometimes the overseas men returned home and married and even then, their wives would not necessarily accompany them to businesses or work abroad. Sometimes their wives would remain in China caring for his elderly parents. Other times, laws in countries like the United States, South Africa or Canada prevented women from joining him. Occasionally, especially if the male settler had earned a fortune, he would bring his family and they would live together overseas. In other instances, overseas men might take a local wife. And sometimes, he had both... a wife in China caring for his parents and maybe his children and a local wife in his adopted homeland.

But Chinese women did migrate too. Not only as wives, but also in their own right.

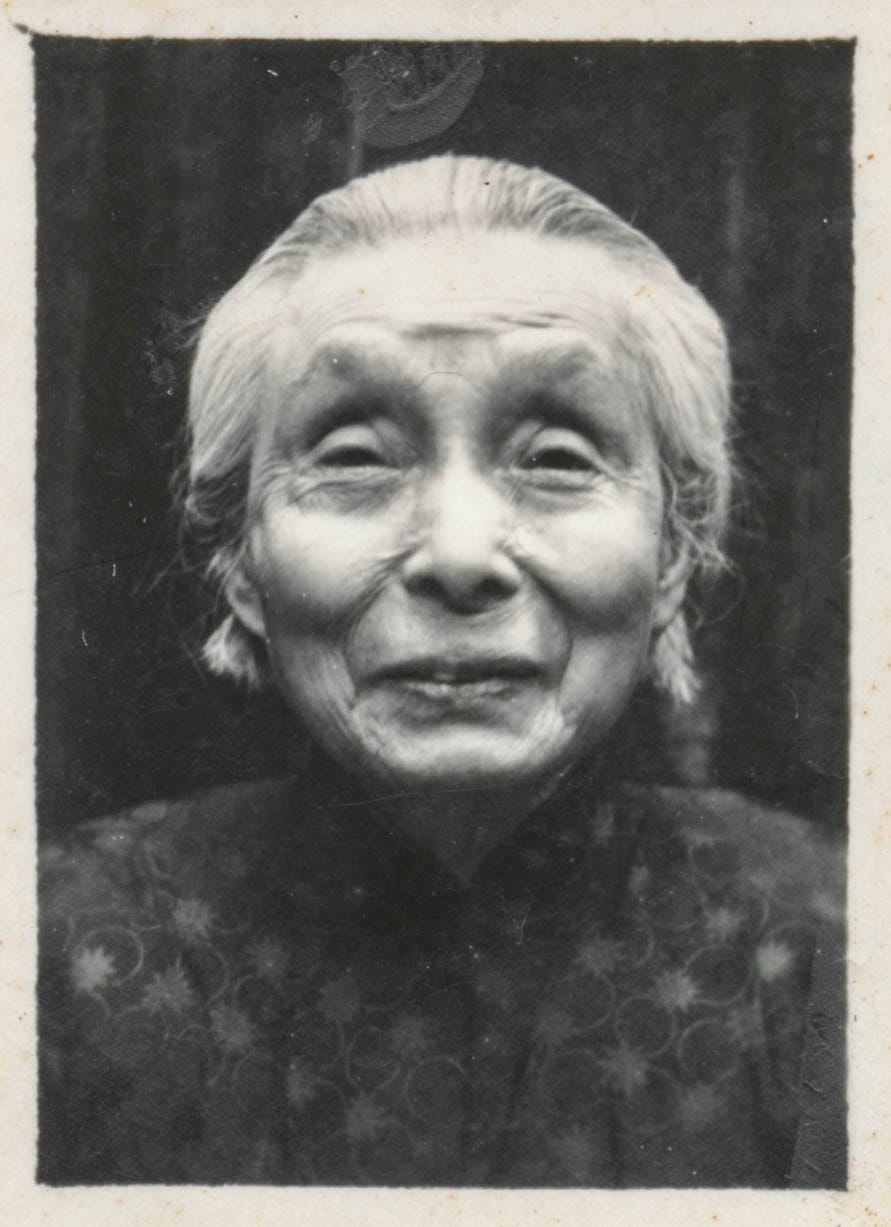

One frontierswoman known as China Mary arrived in Sitka, Alaska in 1895, via Vancouver, at the age of 15. She may have been Alaska’s first Chinese woman. She decided on a husband there and then took over his bakery and restaurant. She learned the Tlingit native language and helped those indigenous women deliver their babies and China Mary learned how to make their silver folk art.

Her husband Ah Bong died in 1902 and after that she supported herself and her two daughters by doing housework for others. For some unknown reason, the businesses she had run were lost. She remarried to Fred Johnson and became a gold miner. She shoveled and handled explosives. She once broke her finger and the bone was sticking out. She then sewed up her skin around the bone and carried on. She and her new husband worked as dairy farmers, prospectors, trappers, trawlers, and fox farmers. She was known for fishing even when no-one else dared brave the elements. She was good with a gun and at seventy years old was still working as matron of the federal jail in Sitka.

A portrait of her shows her in a Manchu dress with embroidery and a ladylike pose. But she certainly was a frontierswoman of tremendous courage and grit.

Other migrants were less well-known.

Mui Tsai is a Cantonese phrase for little sister. They were maid servants bonded to a family. These young women had been born to poor families or unwed mothers and sold to more affluent Chinese families to act as servants or concubines. What their life would be like depended on the family that controlled them. They might be treated as a slave or eventually married off and have a more honourable or comfortable life.

These bonded maidservants were commonly found among affluent Chinese households in Hong Kong, Macao, Singapore or southeast Asia. They usually originated from the coastal provinces of southern China, like Guangdong or Fujian. Those shipped to the USA often ended up working as prostitutes as those who purchased them as Mui Tsai could earn a profit by reselling them for work in brothels.

As a response, the Society for the Protection of Women and Girls was founded in Hong Kong and it was on the lookout for kidnapping of women and children transported into Hong Kong. They had two full-time detectives who would hang out by the waterfront and eavesdrop and check on new arrivals. It wasn’t until the 1920’s and 1930’s that legislation started to regulate abuses of the Mui Tsai and it took until the early 1970’s for the system to end.

There were also paid domestic servants, sometimes called Amah. They were from the river delta of Guangdong province and primarily sent to Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong in the 1930’s. They wore distinctive pigtails and virginal white tunics and black trousers. They were unmarried and, interestingly, operated as a sisterhood, sworn to celibacy.

They were also known as “combed” as they had their hair combed in a traditional ceremony that usually came before a wedding. But in their case, the hair-combing was before a religious ceremony when they were symbolically married to a deity.

They usually worked in silk production and earned reasonable livings through cultivating mulberry bushes, picking the leaves, pulling silk threads and spinning silk. They lived communally with other such women and had their own group social and religious activities.

If they were forced to marry, they sometimes resorted to suicide. In other instances, they used techniques they had learned, like wrapping themselves tightly to prevent themselves from being undressed. Some would then buy their husbands a concubine and escape from any intimate obligations to their husbands. In that case, they might also financially support any children from that other coupling. It seems strange to consider, but it did happen.

Some swore off relationships with men on religious grounds, as physical coupling was considered by them as unclean. Others may have been involved in same-sex relationships. But these sisterhoods were secretive and usually closed to outsiders so there is some doubt. They did create family lines within the sisterhood so that ancestor worship could continue. The living sisters could honour the ancestors who predeceased them in the sisterhood.

They also saved for retirement, illness and funerals and for retirement homes that included farmland where the residents could grow their own food.

190,000 women aged between 18 and 40 immigrated to colonial Malaya between 1933 and 1938 alone. During those 5 years, male immigration was capped by the colonial government and female immigration helped shipping lines fill their ships. Those companies also would sometimes demand 4-5 female tickets purchased for every quota male spot. This helped to close the traditional gender gap among overseas Chinese at least in that part of the world.

The jobs those female migrants found was often as waitresses, cashiers or hairdressers. But domestic work could be more lucrative or honourable, if working for the right family. Baby amahs could be found in parks, caring for the children of European households.

Some women overseas did not need to work. One well-known Chinese woman abroad was Madame Wellington Koo. She was the second daughter of a wealthy Java businessman. Born Oei Hui-lan, in colonial Java, now in Indonesia, she grew up in privilege. She received a gold necklace with an eighty carat diamond when she was three years old. She was later frequently seen in full-length mink coats and ermine capes and loved to have her tiny Pekinese dog on her arm.

She was talented with languages. While her family spoke Hokkien, she picked up Malay from her nurse and spoke it to her father. She learned Javanese from servants and Dutch from some girls she played with. She also learned Mandarin Chinese while visiting Beijing. If that was not enough, she learned French from a maid and English from a governess who also ordered magazines from London, which added to her education. She never attended school but was well polished by tutors.

Her mother sent her to London when she was around sixteen years old and bought a mansion near Wimbledon. Hui-lan had use of a Rolls-Royce and a Daimler to get around.

She and her mother were keen on her marrying well. Most prospective husbands seemed beneath them.

In 1919, a member of the Chinese delegation to the Versailles Conference in Paris heard of her and saw her picture. He inquired about her and Hui-lan’s mother immediately packed her a suitcase for her daughter to travel to Paris.

While Wellington Koo did not have much family wealth, he had been a gifted student at Columbia University in New York and was an up and comer among the Chinese diplomatic service. He was well regarded and would later become the Chinese Ambassador in the United Kingdom, in France and in the United States.

The marriage was mutually enriching. She could support her husband financially, including with the purchase of a home he would not otherwise have been able to manage. And she gained access to Buckingham Palace, the Elysée Palace and the White House that otherwise would have eluded her as the daughter of a successful sugar merchant. She quietly worked to overcome stereotypes and once asked a French diplomat if her husband walked like a coolie and if she shuffled like a bound-foot China doll. They did not.

We will return soon to the Chinese diplomatic scene, especially as we look at China’s neighbour in the direction of the rising sun. Japan was making waves.

This is a fascinating piece of history. Thanks for writing it!