The Fall of the Taiping Rebellion

The Ever Victorious Army, Western Powers and the Legacy of the Taiping

The European powers were not going to help the Taiping. But that does not mean they would not influence them. After all, the Taiping movement had been inspired by a Christian pamphlet distributed in Guangzhou.

And in April 1859, it gained a new leader who had been educated by missionaries.

The Heavenly King, Hong, was looking for an able man he could trust.

Hong Rengan was his younger cousin. He had been involved in some of the earliest activities of the God Worshipper Society. But in 1853, about 6 years earlier, his parents had sent him to be educated in Guangzhou. He learned from a protestant missionary, Reverend Roberts. He then worked for the China Inland Mission. Multiple times, he attempted to rejoin the Taiping and in April 1859, he finally got through. He was greeted warmly and immediately bestowed with honours and titles which made him uncomfortable. He imagined that quick promotion would cause resentment by others.

He was a true believer and well meaning. He was made Chief of Staff and did his best to shepherd the movement at a challenging time almost three years after Yang’s assassination and after years without strategic leadership.

He tried to bring more Christian notions into the movement. He wanted to bridge the divide between the Taiping and the western powers and bring innovations from the west, like railroads and banks to the Taiping.

He seems to have been a keen study. He immediately noticed the lack of religious feeling in Nanjing when he arrived. It was much different than the faith found in the early days.

He published essays trying to reform the Taiping faith and bring it more into line with Christian teachings, while honouring the spiritual beginnings of this movement.

He also shared ideas of modern communication: highways, railroads, shipping lines and other western developments. He wanted to introduce banks and private industry to finance improvements in commerce and communication. He wanted to build insurance systems for life and for property, which would also bring hospitals. He also had ideas for mining that were a form of private public partnership. He also tried to end abuses of alcohol, tobacco and opium that were officially prohibited by the Taiping but in practice had been condoned. He took steps to prohibit gambling and discourage women from wearing makeup or jewelry.

He sided with western criticisms of Chinese practices like infanticide and of family responsibility for the criminal acts of individuals.

He tried to form central control again, which had broken down after Yang’s assassination. But he never did manage to accomplish all that he set out to do.

One challenge was the fickle nature of the Heavenly King’s support. The founder Hong was easily manipulated by others. Those who could lose power seem to have influenced the Heavenly King against his younger cousin.

Two major military commanders were also named king around this time to placate them. The most independent military commander took on the title Loyal King. While the other military commander king seems to have accepted the new chief of staff and worked as part of his administration.

The Chief of Staff tried to bring, in his own words, Rule of Law to the Taiping. He didn’t want personal rule or rule by revelation.

He also reformed the examination system to make it a synthesis of reformed Confucianism and Taiping religion. The successful candidates were to be at the core of his new administration of rule by law.

He also invited missionaries and other western experts to come to Nanjing. He wanted to use their expertise to improve the Taiping territories.

However, his efforts were undermined by the Heavenly King who never bought into them. Western audiences were also sceptical and asked the Chief of Staff if his ideas truly had the support of the other kings. One well meaning king was not enough. When visitors did come, the Heavenly King turned them off with his own treatises, his belief that he was divine ruler of the world and, in the words of missionaries, “revolting idolatry”.

By 1860, the Anglo -French Expedition, also known as the Second Opium War, had ended and European powers were no longer at war with the Qing. They had gained favourable peace terms and wanted to develop new trading opportunities. A civil war, with shots accidentally being fired on British ships, was not what they wanted.

The new central leadership did have one clear effect. To break a new siege of the capital, all the commanders conferenced together beforehand and developed a plan that worked. It had a diversionary move towards Hangzhou, which caused the Qing general to remove some troops. The diversion then quickly reversed course and attacked the government camp from the south while another army which had been at Anqing rushed back and attacked it from the north. The siege was broken.

The Chief of Staff then got the military kings to agree on the next steps. Rather than act independently to fight for their own areas of control, he got them to agree to a larger mission. First, they would attack downriver and take Hangzhou and Suzhou to relieve the Taiping rear and to enable supplies from the westerners at Shanghai. Then each commander was to proceed west on each side of the Yangtze River in a pincer movement to trap the Hunan provincial army.

The campaigns started well enough, and the cities were captured downriver from Nanjing. The northern army then also carried out its plan. However, the so-called Loyal King’s troops south of the Yangtze eventually disregarded the plan and did not meet up to battle the Hunan provincial army. He moved away and strengthened his base instead. The provincial army thus only had to face the Taiping on one side, and it defeated its northern attacker.

This defection from the strategic plan by the so-called Loyal King was short-sited as he eventually would be captured by Zeng and interrogated. All captured Taiping leaders were given the chance to give a detailed confession (essentially an autobiography) before execution. His explanation for his actions is one of the documents from this time. His excuses for this mistake were weak and it seemed like he couldn’t prioritize the larger struggle to his own short-term position. In the end, that cost the entire Taiping effort as both army groups were eventually defeated.

The so-called Loyal King later made things worse by attacking Shanghai, when urged not to by other Taiping leaders. His disloyalty is best explained by his hatred of the Chief of Staff, who he considered beneath him and by his self-reliance.

The Chief of Staff also caused hostility in the Heavenly King’s two brothers who had been pushed aside and they seem to have influenced the Heavenly King again against his cousin.

The Chief of Staff was demoted to Assistant Chief of Staff, and he lost control of the official seal for official proclamations.

The Heavenly King now ignored matters “of this world” and focused on heavenly matters, like renaming the Great Peace Heavenly Kingdom to the Lord’s Heavenly Kingdom, which everyone else ignored.

A new power struggle in Nanjing began through control over The Young Monarch, the Heavenly King’s son in his early teens. Different players tried to use him for their purposes.

The so-called Loyal King was focused on developing the areas he controlled. He instituted an internal customs duty and kept most of the tax revenue from his district. Landlords were welcomed back and taxed. This Taiping king did sometimes send food and funds to the capital, especially when asked and when he went there in person, he disgorged some of his personal funds for the capital. But the days of a common treasury were long-gone.

There was now essentially a government backed provincial army against a Taiping backed provincial army, each with a warlord at its head and each keeping most of the revenue generated from the territory.

The westerners believed the Taiping were living off loot and being excessive in the burning and destroying of towns and villages.

Zeng noticed the disintegration of the Taiping, while the government side was strengthening. Two new provincial armies were raised and there were now three such armies descending on the Taiping.

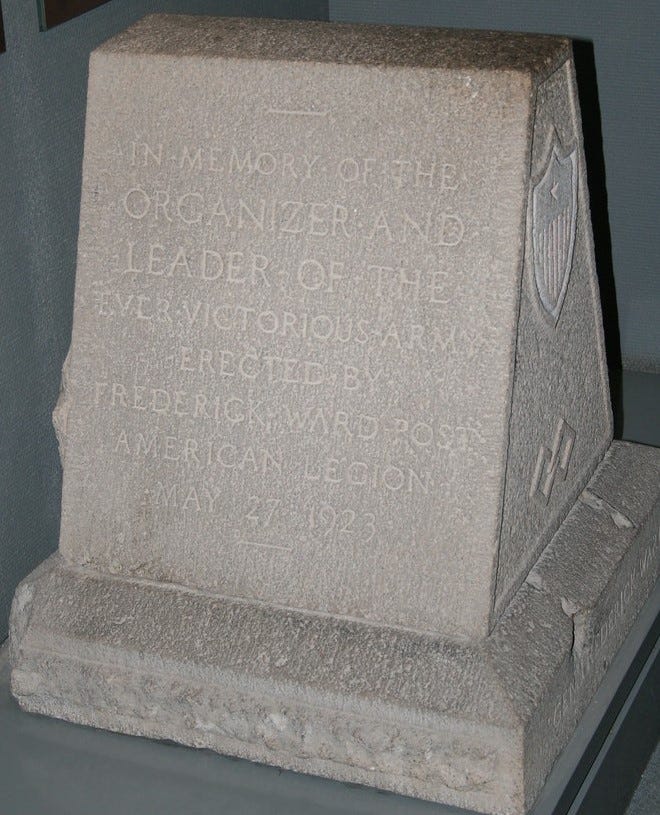

One such provincial army operating on the lower Yangtze River around Shanghai was benefiting from foreign trade revenues. It also partnered with Europeans who were keen for the civil war to end. The foreigners’ army, let by Major Gordon was called The Ever Victorious Army, but that was a misnomer. It suffered numerous defeats to the Taiping, including one where Gordon was seriously injured. Its pay was usually in arrears, so it had trouble keeping soldiers. Gordon also quarrelled with the head of the Chinese provincial army there. Gordon had given his word that Taiping that surrendered would have their safety guaranteed. But the Chinese provincial army head instead executed the leaders. This infuriated Gordon. It did have some victories and made a difference in the lower Yangtze River. But it was disbanded in May 1864.

Two months after it was disbanded, on July 19, 1864, a siege of Nanjing finally succeeded. It was led by Zeng’s brother. The fall of the Taiping capital was expected, and the Young Monarch and some other leaders escaped. The Heavenly King had already died on June 1, 1864, so his death was 6 weeks before the fall of his capital. He died after 20 days of illness, and some suspect he might have taken poison. Initially, the Taiping founder’s death was suppressed, but then the Young Monarch was placed on the throne.

The fall of the capital led directly to at least 100,000 dead. Not one of the Taiping surrendered and either fought or killed themselves. Often, they did so by fire, which caused additional destruction in Nanjing.

The Young Monarch had been outside of the Heavenly Capital when the city was lost. He may have been out to recruit new troops. With the fall of the city, he fled to Huzhou where he joined a Taiping warlord in charge of the area. While strong militarily, he was terrible administratively and his army seems to have been entirely funded by looting.

When provincial armies descended on that city, the Young Monarch and his followers fled to Jiangxi province, where they were hunted down and captured one by one. By November 1864, they were all dead.

There were still some independent commanders in the field, and they had gotten used to operating autonomously from the heavenly capital. They were still prohibited from surrender so they fought on as best they could.

The remaining Taiping leaders south of the Yangtze River generally moved south. One went towards Xiamen on the coast, where he was able to get some foreign weapons and adventurers to join him before being defeated. Another went to Guangdong, where he gained some new Hakka recruits before being defeated in February 1866.

North of the Yangtze, merging the remaining forces with the Nian rebels allowed these Taiping to carry on longer. The Nian split in two. The Eastern Nian ended up retreating to Shandong province southeast of Beijing and falling by January 1868. The Western Nian were never able to reach the Muslim rebels they wanted to work with. They too were forced towards Shandong province and were annihilated by August 1868.

Zeng had committed to exterminating the Taiping. He was successful in that the movement never returned once the leadership and core group died. Zeng defined the hard core as anyone who had joined the movement in Guangdong or Guangxi provinces, when the religious zeal was strongest. Others who had joined or been forced to join after had some hope of surrender.

With the Taiping Rebellion over, we can see a few long-term trends. A major development was the creation and growth of regional warlords. Another was the alliance of the western powers with the weakened Qing Empire, once the Anglo-French expedition was over. The western imperial powers wanted trade and concessions and believed a continuation of the weak Qing Empire was best.

Some innovations by the Taiping would be seen again, like the simplification and updating of the Chinese language and the introduction of a 7-day week. While formal simplification of Chinese throughout China would come later, and the modern calendar is associated with the Republic of China, we did see those elements in the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. The tensions between Confucianism and modernity, especially with the influence of the western powers would also be seen again. And the growth of regional warlords will be of great relevance in the coming decades.