In the Qing dynasty, government administration was coveted employment. The empire was large, powerful and sprawling. It governed an area larger than today’s China, from a northern capital at a time before telegraphs, telephones or other modern communications. Messages were sent by post. That could take weeks depending on the distance. Regional administrators were important and powerful.

The Chinese system, which had lasted for many dynasties, was based on the Examination System.

To be a senior administrator, one had to pass three successive and grueling examinations. These examinations were about mastering classical and Confucian teachings. Successful administrators had to be knowledgeable about poetry, the classical arts and lessons of governance and philosophy almost 2000 years old.

During the Qing Empire, around two million candidates sat for the lowest level of examinations at the county level. Candidates could sit twice every three years.

But it had a pass rate of around 1.5%.

The next level, the provincial stage, had a 5% pass rate.

The final, metropolitan stage, had a 1.5% pass rate.

As the population increased, those ratios may have worsened further.

In 1699, a 100 year old man was still trying to pass the exam and was brought into the exam room by his great grandson who was trying it for the first time.

Revolts were often led by failed examination candidates. For example, the Ming Dynasty’s end was caused by insurrections led by a failed examination candidate. The Taiping Rebellion, which will be discussed soon in this podcast, was led by a provincial schoolteacher who had repeatedly failed the civil service examinations and may have suffered a mental breakdown as a result.

There were a lot of ambitious but unsuccessful examination candidates in Qing China.

Under the Qing Empire, there was also positive discrimination in favour of ethnic Manchu candidates. They benefited from quotas and an alternative examination system. They could choose to translate passages from the classics and pass an archery test instead of the traditional exams.

Bribery by those who did pass the Examinations and get an official post was also a major issue in the Qing Empire.

An infamous case was Heshen, a favourite of the Qianlong Emperor (grandfather of the Daoguang Emperor who was on the throne during the Opium War). Heshen was a top administrator for 26 years and was in charge of 4 key boards, including Civil Office, Revenue, War and Punishments. He also supervised the palace examinations. After he was impeached in 1799, an official, conservative estimate calculated his assets to be worth twice that of the government’s annual budget and he possessed more than ten million ounces of silver, 600 pounds of top quality ginseng, 550 fox hides, 850 racoon hides, 56,000 sheep and cattle hides, 460 European clocks, thousands of estates and residences and had 600 concubines. Ultimately, he obeyed the Emperor’s command to commit suicide and his property was confiscated.

But corruption and patronage were widespread. In the early 1800’s, for example, six million taels of silver were allocated each year for the Yellow River Conservancy. But only 10 per cent found its way to the public project according to estimates.

Corruption was so expected that less corrupt ones sometimes had to appear to be corrupt to have social status. One notable case was when a less corrupt official retired and moved back to his home community. His family filled boats with eighty wooden crates loaded with bricks so that locals would think it was the riches he had hoarded over his five-decade long career.

As we move next into the Opium War and then the Taiping Rebellion, and later to the fall of the Qing dynasty, it is good to keep in mind the Examination System and the unhappy failed examination takers. As well as corruption by successful officials and the distinctions between the Manchu and other ethnicities, like the Han majority.

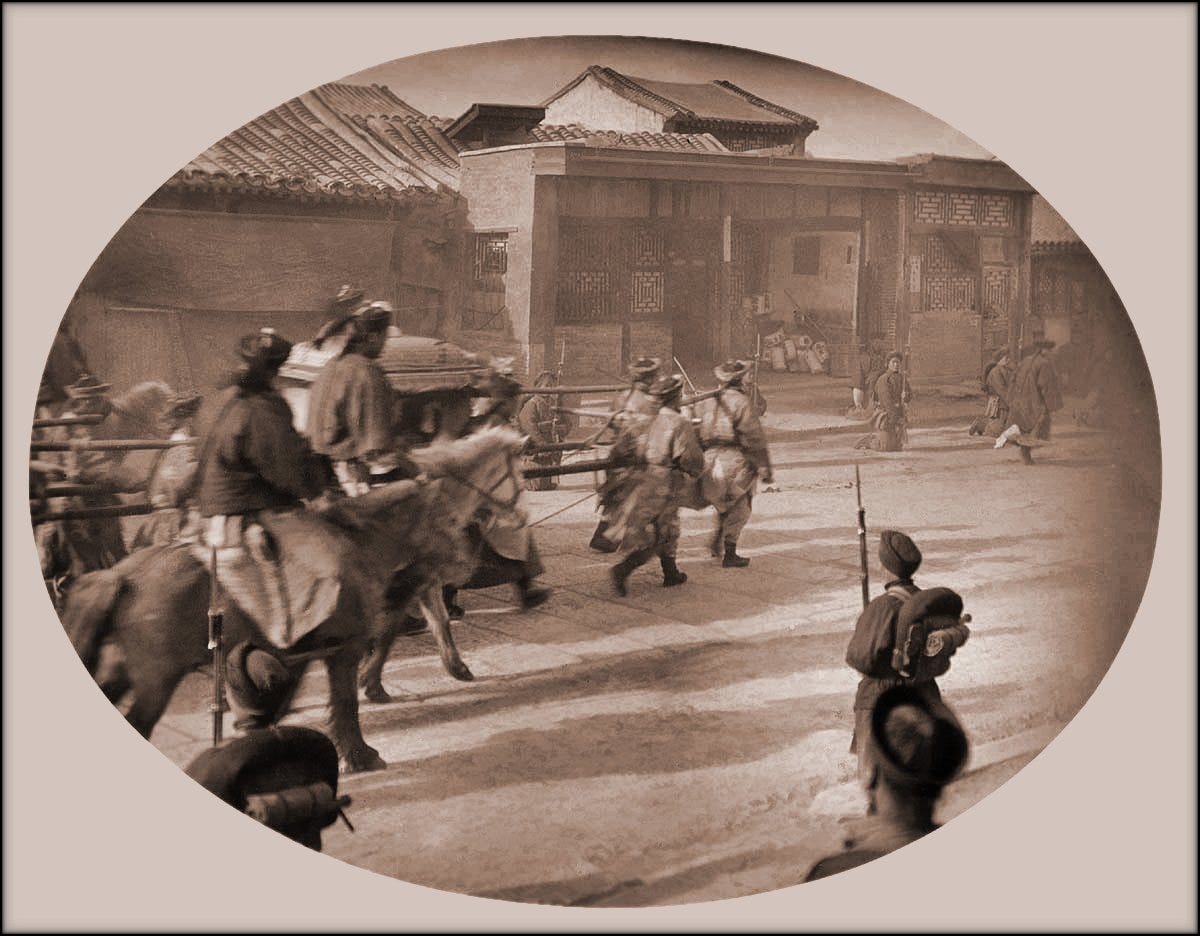

Image: "Qing Court Return, The Emperess Dowerger [1902] George E. Morrison [RESTORED]" by ralphrepo is licensed under CC BY 2.0.