Last time, I mentioned that more than 200 million Chinese lived under Japanese occupation during the Second Sino Japanese War. More than any other lived under Wang Jingwei’s puppet regime in east China.

We’ve met Wang Jingwei before. He tried to assassinate Emperor Puyi’s Regent during the last days of the Qing Dynasty. Wang Jingwei wrote Sun Yat sen’s political testament. He was seen as Sun Yat sen’s successor before Chiang Kai-shek achieved greater success with the Northern Expedition, which brought the Nationalists to power in China. For a time after that, Wang still honoured the first United Front between the KMT and the Communists and tried to operate a Chinese capital out of Wuhan. But like Chiang, Wang Jingwei then also turned on the Communists and believed the Nationalists would be better off without them. But how did this one-time leader of China’s Nationalist Party come to a deal with the Japanese and become a collaborator and, as result, become infamous. He is considered a hanjian (traitor to the Han nation) and kuilei (puppet) by Chinese historians as well as by the public.

Let’s have a deeper look at Wang Jingwei now.

Born in 1883, his real name was Wang Zhaoming, but he was better known by his pen name: Wang Jingwei. Like many bright students during the late Qing period, he studied in Japan. He was handsome with movie star good looks. He was interested in politics from a young age and always saw an important place for himself. Wang Jingwei learned Japanese during his time studying in Japan. There, he studied political science and law at Waseda University in Tokyo. Wang spent five years in Japan, from 1903 to 1908, which included the time when Japan defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War. Wang would have been immersed in the Japanese language and culture. He cut off his queue, a symbol of Manchu domination, and became a Chinese nationalist. Wang was imprisoned after he attempted to assassinate the Prince Regent, father of the boy Emperor Puyi. Wang interacted with Yuan Shikai’s son Yuan Keding and then Yuan Shikai too and tried to get Yuan to see the benefit of a republican government for China.

Wang Jingwei was a close follower of Sun Yat sen and was with Sun on his deathbed. It was Wang who wrote Sun’s political testament and Wang was the leader of the Kuomintang, China’s Nationalist Party, in the immediate aftermath of Sun’s death. Wang was considered on the KMT left and during Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Expedition, Wang Jingwei was allied with Chinese Communists and set up a government in Wuhan that was in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek when Chiang broke with the Communists during that expedition and set up Chiang’s administration in Nanjing. But then Wang Jingwei also broke with the Communists.

Wang, not for the first time, went into exile in France and then allied with Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan on the losing side of the War of the Central Plains. Wang then had an on again- off again relationship with the KMT over the next years. Sometimes he went into exile in Europe, officially for his health, and sometimes he was an important KMT leader in Nanjing. He was Premier in 1932 when Japan attacked Shanghai and after that. Wang was President of the Executive Yuan and Foreign Minister for much of 1932 to 1935. Chiang’s power rested in his position as leader of the government military. Chiang also controlled intelligence flow, which often kept Wang in the dark on important topics. Wang supported the KMT policy of “first internal pacification, then external resistance”. That meant that Wang supported Chiang’s attempts to defeat the Communists first before turning focus to Japanese aggression. Wang’s support for Chiang’s policy during the early 1930s strengthened Chiang and helped him launch his encirclement campaigns against the Communists. Wang did have influence and, with Chiang often away because of the Encirclement Campaigns, Wang did have quite a bit of room to maneuver, especially with regards to Japan. Chiang was out of Nanjing for 8 months of 1935 during the successful final encirclement campaign of the Jiangxi Soviet. However, Chiang was in contact with Wang by cable.

Importantly, Wang Jingwei was more pessimistic towards resisting Japan than Chiang was. Wang believed that foreign powers would never intervene to help China against Japan. Chiang Kai shek was more optimistic on that front. In the end, both the USA and finally the Soviet Union did help defeat Japan. Chiang Kai shek saw what Wang would not. Japan’s aggression would, in the end, create allies for China. In speeches to Chinese officers in 1934, Chiang stated that Japan’s expansion into China as well as along the coast south, would eventually antagonize some combination of the Soviet Union, Great Britain and the United States. Chiang was right. But it took longer than Chiang would have liked, and only after Japan attacked Great Britain and the United States in December 1941. Only once they had been directly attacked at Hong Kong, Shanghai’s international settlement and at Pearl Harbor, almost all at the same time, were Britain and the USA finally at war with Japan.

Wang had been more pessimistic. He saw the failures of the League of Nations to mean that China could not rely on foreign powers to help defend China against Japan.

After Japan attacked Shanghai in 1932, it was Wang who led the negotiations with Japan for China. He had similar roles as negotiator as Japan slowly pushed forward in north and northeast China beyond Manchuria. In 1935, Wang survived an assassination attempt and returned to Europe to recuperate. Just before that, he had been an advocate for China joining Nazi Germany and Japan in the Anti-Comintern Pact. Chiang Kai-shek was much more flexible in his thinking and was open minded about his options for national defence and had feelers out both with the Soviet Union and with Japan to see what terms he could get.

It seems like the motivation for the attempted killing of Wang Jingwei was his perceived weakness towards Japan. The would-be assassin told the police he targeted Wang because of Jingwei’s views towards Japan. It also seems as if the assassin had connections with the army group that had fought Japan in Shanghai in 1932.

Wang Jingwei still considered himself a follower of Sun Yat sen and seems to have believed that he, not Chiang Kai-shek, was the true successor of Sun. Within the KMT, by the mid 1930s, Wang was viewed as being among the most pro-Japanese. Wang’s view was that “national salvation” meant making peace with Japan and trying to build China with Japan against communism.

Wang opposed the second United Front between the KMT and the Communists against Japan. He returned from Europe in early 1937, after Chiang Kai-shek had been released following his kidnapping in Xian. Wang did not retake his previous high-ranking positions in the Nationalist government, though he did still have a leadership position in the KMT political party.

In 1938, Wang left Chongqing for Hanoi and made clear that he preferred a negotiated peace with Japan.

He then became a self-appointed peace representative. There had been some unofficial peace negotiations happening with Japan, but without Chiang Kai-shek’s official sanction. The sources I read suggest that the Chinese persons negotiating with Japan had permission from Chiang Kai-shek to be spying on Japan, but without authority to be negotiating. Japanese officials had some interesting in negotiating an end to fighting with the Republic of China. It seems they would have liked to consolidate their gains without further war. But Chiang Kai-shek was unwilling to come to terms and diplomatic relations between Japan and the Republic of China deteriorated.

Wang seems to have been a very poor strategist. He picked the losing side repeatedly. At least one writer has described Wang as "negative, passive, and escapist”. He certainly had a history of running away when things got heated. He had done so after Chiang’s maneuvers after Sun Yat sen’s death, again after the Northern Expedition, after the assassination attempt and during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Wang had no real leverage with Japan and did not accomplish the goals he set out in the negotiations. He set up a second Nationalist regime in occupied Nanjing, but at first not even Japan recognized it. The Japanese authorities were holding out for a negotiated agreement with Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalist government in Chongqing. They believed forming another Chinese government would interfere with such negotiations. That helps explain the gap between Wang’s defection from Chongqing in late 1938, the setting up of his government in Nanjing in March 1940 and its eventual recognition by Japan in November 1940. Inukai Ken was a Japanese man who supported Wang Jingwei. He reflected bitterly that Wang was like an uninvited guest attending a banquet at which the guest of honour was delayed. Only when it became clear that Chiang would not sign a peace treaty did Japan recognize Wang Jingwei’s Reorganized National Government in Nanjing about half a year after its creation. From that point on, there were two Nationalist Governments using KMT symbols. One was led by Chiang Kai-shek in Chongqing, at war with Japan. The other was led by Wang Jingwei in Nanjing under Japanese occupation.

Local Japanese military commanders preferred to administer their areas of China and did not want to give up control, even to a figurehead. It was because the military command in north China kept control of the north that the Wang Jingwei government only ever had a fictitious role in northern China.

The basic treaty, negotiated by Wang and his team in November 1940, granted almost no powers to the Chinese and held almost all by Japanese authorities. Problematically for Wang, that basic treaty also included the Reorganized Government’s formal recognition of the Empire of Manchukuo, something Chiang’s KMT never did. And the text of that treaty was leaked early on, undermining Wang Jingwei’s credibility from the start of his regime.

Wang’s government claimed all of China and called itself the inheritor of the Xinhai Revolution and Sun Yat-sen’s legacy. Wang Jingwei stressed the need for a period of extended peace for China to elevate itself economically and militarily to the levels of its neighbor and the other Great Powers of the world. Wang Jingwei’s regime accused Chiang Kai-shek’s National Government, which had taken refuge in Chongqing, of playing into the hands of the communists by prolonging a hopeless war.

But when peace didn’t come to China, Wang’s messaging evolved. The Reorganized Government became more closely aligned with Japan’s Asian Co-Prosperity movement and against the “Anglo-Saxons”. Selected Chinese students went to study in Japan with Japanese guidance and support.

As one scholar has put it, Wang Jingwei’s regime was theatre. It was pageantry. It appeared on camera as a government, but it was just stage acting. The Wang Jingwei Regime increasingly took on the imagery and symbols of fascism. But being a puppet regime, it had no real army or navy. It was wholly dependent on Japanese permission to exist and what ships it received were from Japan. Two captured Nationalist cruisers were handed over to Nanjing by the Japanese and were used for propaganda. However, the Imperial Japanese Navy took them back in 1943 because it needed them as the Pacific War was not going well for Japan. The only military activities the regime took on were parades for the camera and anti-bandit and anti-guerrilla campaigns in the countryside, which suited Japan who was struggling to contain guerrillas.

The Reorganized Government had virtually no powers under its “basic treaty” with Japan signed in late 1940. What reality there was, beyond the stage acting of Nanjing, were the negotiations behind the scenes between Wang and Japanese authorities. Wang always wanted more authority, more power, more weapons for his administration. For almost the entire period of the war, the Japanese power players resisted. They saw no reason to give Wang anything, certainly not autonomy or a navy or any of the things that Wang requested.

Before Pearl Harbor and the Pacific War, the Japanese ensured that taxes and duties collected by the foreign powers in the International Settlements in Shanghai were kept within Japanese control, officially on behalf of the Nanjing government. This cut off an important source of revenue for Chiang Kai shek’s government. It was the Japanese military who mostly spent these duties and taxes.

One area where the Japanese Army did want assistance was in the countryside, resisting guerrilla warfare. In January 1941, the Japanese Army drew up guidelines, which divided North China into secured, quasi-secured and unsecured regions. In the secured regions, Chinese collaborators were organized to form a police force to take over local security; in the quasi-secured regions, a piecemeal approach was followed to create no-man’s-lands that were gradually turned into secured areas. In the unsecured regions, military raids were the main policy, along with the Three Alls (Kill all, burn all, and loot all) and the policy of encirclement.

The aim was to increase the secured regions from only 10 percent to 70 percent of the total land occupied by the Japanese within three years. That is a startling admission. The Japanese Army was saying that in early 1941, it had only secured 10 percent of the Northern Chinese land that it had captured outside of Manchuria.

There was resistance and guerrilla action against Japan not just in northern China but also in the mid and lower Yangzi River valley, which was the heartland of the Reorganized Government. That was a main motivation for Wang Jingwei’s countryside purification campaign. The other would have been Wang’s hostility towards communism. Japanese forces, as well as Reorganized Government troops under Wang Jingwei’s leadership, targeted villages suspected of harboring guerrillas. They burned homes, crops, and infrastructure. This strategy aimed to deny resources to the resistance and to intimidate locals.

The units hunting guerrillas conducted sweeps, arrests, and executions. The “pacification” campaigns sought to suppress resistance. The Japanese relied on local collaborators to identify guerrilla hideouts and leaders.

Often, in response to a Japanese casualty, reprisals were carried out against civilians. Entire villages faced collective punishment. This then created a cycle of resistance, violence and reprisals.

This has been described as the Three Alls policy. “Kill all, burn all, loot all.” That would be a scorched earth strategy in retaliation for action against the Japanese. Japanese nationalist groups deny that such a policy existed.

The Japanese Military Police Corps, the Japanese Special Higher Police, collaborationist Chinese police, and Chinese citizens in the service of the Japanese all worked to censor information, monitor opposition, and torture enemies and dissenters. A "native" secret agency was created with the aid of Japanese Army "advisors".

In June 1941, Wang travelled to Tokyo to try to negotiate additional powers. That trip failed, in part because that was when Hitler began his invasion of the Soviet Union and Japanese military leaders felt emboldened and imagined that total victory in China would be possible.

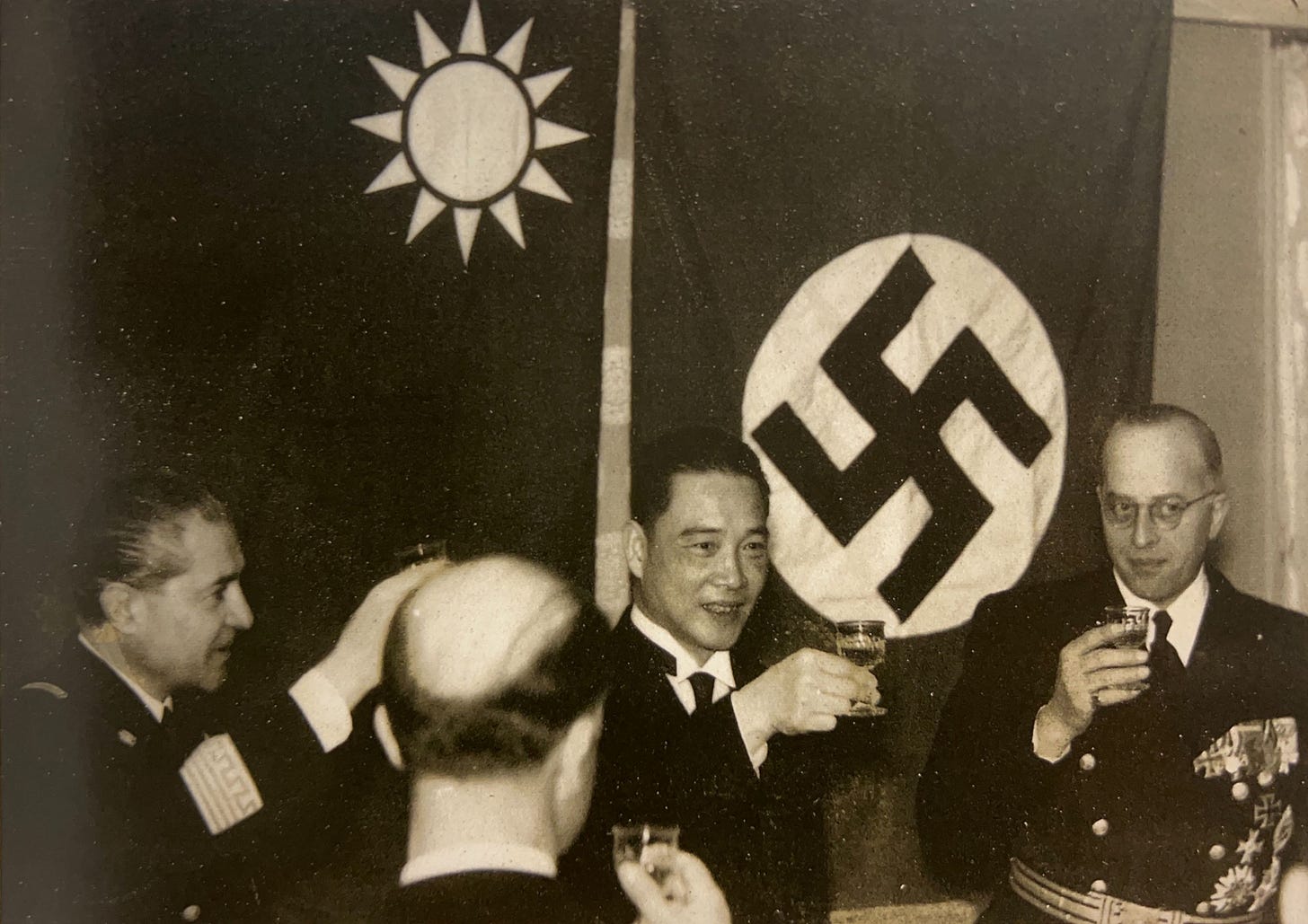

In July 1941, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy also recognized the Reorganized Government in Nanjing as China’s national government. In November 1941, the Wang Jingwei Regime officially joined the Anti-Comintern Pact.

But as the Pacific War started to go badly for Japan after the Battle of Midway, the Japanese government began to value allies and wanted relief for its overstretched forces.

A Sino-Japanese Treaty of Alliance was signed in October 1943 to replace the “basic treaty”. It officially provided for mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, close economic cooperation as equals in establishing a Greater East Asia. In a protocol to the treaty, Japan agreed to remove all its troops from China as soon as the war was over.

Only at that point did Wang’s Regime gain some autonomy. For example, control over the opium policy in the Japanese controlled areas of eastern China. The Wang Jingwei regime announced that imports of opium from Japanese controlled Inner Mongolia would be halved.

From the beginning of Wang Jingwei’s negotiations with Japan, his government wanted control over opium. Its goal was two-fold, to control its distribution and use and to receive tax revenue from it. But until 1943, it was denied any control and required to do as commanded by Japanese officials. Opium cultivation and use grew in occupied China.

The Wang Jingwei government, in response to Japanese requests, had reduced the criminal punishments for the opium trade, which had been strictly punishable during the KMT’s decade in power. In its play-acting theatrics, Wang Jingwei’s Regime continued to honour Opium Suppression Day on June 3rd and honour Lin Zexu who had destroyed thousands of crates of British opium that he had confiscated around the time of the Opium War.

The opium during the Second Sino Japanese War came from a variety of sources. The major domestic source was Inner Mongolia, where opium revenues sustained the puppet regime; but there were other domestic sources within Japanese controlled China. The source for imported opium was Persia, which was important in the early years of the Japanese controlled monopoly system. However, the outbreak of the European War in 1939 reduced the flow of Persian opium, and the onset of the Pacific War saw imported opium virtually cease.

There was widespread planting of opium by the peasantry in Japanese occupied areas. Opium cultivation was lucrative and encouraged by local officials. Opium poppy had become important in those rural economies from which the puppet provincial governments and the Japanese military received important financial benefits.

It is understood that Prime Minister Tojo used profits generated by the sale of opium in Japanese controlled China to bribe Japanese officials.

Even when Wang’s Regime assumed control over opium in 1943, it understood it needed Japanese co-operation to stop smuggling. The Wang Jingwei regime did not really control its territory. Although it did get the agreement of senior Foreign Ministry and other government officials, this did not mean compliance by Japanese military units and agencies. They continued to profit from the opium trade. And the Reorganized National Government had to balance opium suppression with revenue generation.

In March 1944, Wang went to Japan for treatment of a wound left over from one of the assassination attempts on his life. Later that year, he died in Nagoya, Japan. After Wang Jingwei’s death in 1944, Chen Gongbo took over as President.

The end of World War II saw the dissolution of puppet regimes, the repatriation of Japanese settlers, and the reintegration of the former puppet territories into the Republic of China, as agreed upon in the Cairo Declaration of 1943.

The Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China at Nanjing was dissolved at the end of the war and many of its leading members, like President Chen Gongbo, were put on trial and then executed for treason. Chen was executed in 1946 by Chiang’s KMT government. Wang Jingwei’s name has become synonymous with treason in Chinese history.

After the war, Japanese opium and narcotics operations in China were one of the war crimes punished at the International Military Tribunal for Tokyo. “Narcoticizing the people” was one of the charges against Chen Gongbo, who was President after Wangi’s death.

Today, most Chinese remain firmly opposed to narcotics and I am not aware of any significant efforts to legalize marijuana in China. The People’s Republic is strongly against the legalization of drugs like marijuana. The legacy of opium in China is still strong.

One consequence of China having been divided into different spheres during the Second Sino-Japanese War is how Chinese soldiers were treated after the war. Unlike in the West and in the Soviet Union, Chinese soldiers were not considered heroic after the war. When the Communists won the subsequent Chinese Civil War, there was no blanket respect for veterans of the Sino-Japanese War. Unlike in the Soviet Union, there were few Veterans organization and almost no blanket respect for former soldiers. In some cases, an important question was which army you had fought for. Much turned on which part of China you were in and whose government you had served under.

Until 1982, the Communist Party generally didn’t distinguish between Wang Jingwei’s Puppet Regime in Nanjing and Chiang Kai shek’s KMT government in Chongqing. During and after the war, the Communists tried to delegitimize Chiang’s KMT by associating it with the Wang Jingwei regime. It was not until the emergence of a ‘new memory’ of the Sino-Japanese war in 1982 that the Chinese Communists recognized the contribution of the KMT to the resistance, drawing a clear line between Chiang and Wang. It was only once Beijing began to consider peaceful reunification with Taiwan that its messaging about the KMT’s role during the Second Sino-Japanese War evolved. No longer had the KMT been traitors. Since then, the term hanjian, or traitors to the han nation, has been reserved for true collaborators, like those in Wang Jingwei’s Reorganized Government of Nanjing. Wang was a leader of a so-called Puppet State and has the worst of historical reputations in China today.

Until the mid-1980s, mainland China historians explained collaboration in terms of social class. The collaborators were synonymous with pro-Japanese elements within the class of big landlords and big capitalists.

You can also imagine the uncertainty which ordinary Chinese must have felt given the constant change of governments. During China’s Warlord Period, there had been numerous changes of control. Then with his successful Northern Expedition, much of central and eastern China came under Chiang Kai shek’s control for the Nanjing decade from 1927 to 1937. Some areas in Jiangxi and elsewhere also experienced changes of control between the Communist Soviets and the KMT, after its successful encirclement campaigns. But then with the advancing Japanese, about 200 million Chinese lived under Japanese occupation in the various puppet states.

With the end of the war and with Japan’s surrender, Chiang Kai shek’s KMT was given control again, only to lose it during the Chinese Civil War. I can only imagine the feeling of whiplash and of uncertainty as the Chinese experienced one regime after another. It must have been deeply unsettling. Leaders like Wang Jingwei clearly were collaborators with Japan. But for ordinary people, living under Japanese occupation rather than fleeing to western China to be bombed, or fleeing to the countryside to join the guerrilla fighters, might just have felt like survival.