Yuan Shikai and the Xinhai Revolution

Yuan Shikai Ended the Qing Dynasty after the 1911 Revolution

Yuan Shikai served multiple roles in the late Qing Dynasty. While Governor General of Zhili province, Yuan was also in charge of spreading military reforms throughout the country.

After the Boxer Rebellion, he founded the Baoding Military Academy, as well as other military training schools and officer training academies. Some of the promising students of the military academies were sent to Japan for further studies. One such student was Chiang Kai-shek, who later headed the KMT political party and was President of the Republic of China. Special military schools for Manchu nobles and high-ranking Han officials also existed.

Yuan’s army became known as the Beiyang Army and became the model on which other provinces’ armies were standardized.

There was a regular army, as well as two reserves. Generally, troops were to be cycled down from the regular army into the reserves. This helped to push previous green standard army members into the reserves and replace the weak with the strong. Officers were exempt from this rotation and would stay in the regular army for longer. Pay was decreased as one passed into the reserves and returned to one’s hometown.

The Troops Training Administration was formally headed by a Manchu noble. But really, Yuan controlled it and used it as a command center.

Only the Imperial Guardsmen were still tested with the bow under the old Manchu preferential test discussed in the post on the imperial examination system. The Imperial Guardsmen were Manchu and they protected the Royal Court wherever it travelled.

In some cases, the new provincial armies were not controlled by Yuan but by local officials.

By the time of the 1911 revolution, there were “new armies” throughout China modeled on Yuan’s reformed New Army.

In 1908, the Guangxu Emperor and the Empress Dowager died within a day of each other. Pu Yi became three-year-old emperor and his father Zaifeng became Regent. Almost immediately, he dismissed Yuan who fled to the foreign concessions in Tianjin in fear of his life. Once it was clear that Zaifeng would not also kill him, Shikai returned to Chinese controlled territory, made an appearance at the palace to thank the court and then retired to his home province with his wives, children and servants. Together, they numbered more than 200 people. He did not return to his hometown since he had fallen out with his elder brother who refused to allow Shikai’s mother, a concubine, to be buried next to her husband.

Why was Yuan dismissed by the Regent? There does not seem to be any evidence that Shikai had actually poisoned the Guangxu Emperor. Records seem to show that Yuan was not near him at the time of his final days. That did not stop Kang Youwei from immediately accusing Yuan of the murder of the emperor. But Kang was not in China and that seems to have been propaganda and his way of getting back at Shikai for his role in supporting the Empress Dowager during the 1898 coup. Kang Youwei did write privately to the Regent calling for Yuan’s removal to avenge the late emperor. Likely Zaifeng also blamed Shikai for that. Zaifeng was the younger brother of the late emperor and must have known that the emperor hated Shikai for that betrayal.

With the Empress Dowager gone, there was a re-assertion of Manchu nobles. They dismissed Han Chinese officials, who they did not trust. Such moves seem short sighted as Sun Yat-sen and other revolutionaries were promoting an anti-Manchu and pro-Han nationalism. The fewer opportunities that existed for Han officials within the system, the more likely they would support an alternative to the Qing.

Sun was delighted by Yuan’s sacking. Sun didn’t expect the Beiyang Army to come over to the revolution’s side. But he thought that their loyalty to the Qing would be weakened.

Yuan had not helped himself by celebrating an extravagant 50th birthday party, using the traditional Chinese way of counting years, in September 1908. It is said that stores in the capital, Tianjin and close to Yuan’s army base were all sold out of gifts as a result. That was before the Empress Dowager died. Within a few months, he was dismissed.

Yuan Shikai lived quietly in retirement for more than 2 years. The Qing kept an eye on him, to ensure he did not cause problems. He invested in businesses, like a textile mill and a silver mine. One investment was in a new water venture for Beijing. The capital had relied on artesian wells for water. Now, clean water was piped in and Shikai profited from it. He acquired more land around his home. He wrote poetry and built a garden. His health had suffered when he held many positions for the Qing and he did work on regaining it.

He had one wife and 9 concubines. He hired teachers for his 32 children and allowed his concubines to be educated. The curriculum was a mix of Chinese learning, science and western subjects.

He was careful to not cause trouble. Of the 750 letters he wrote during that time, the majority were replies when others wrote him. 625 of them claimed he was slowly recovering his health. He did not ask for favours and generally declined to help others. Some sent him monetary gifts at the time of his daughter’s wedding and brother’s death. He returned the funds.

His poetry had improved and was included in a publication of Poems by Famous Ministers in mid 1911, before that year’s revolution. The author praised Yuan’s poems.

Shikai funded refurbishment of a public park in northern Henan province and donated to schools. He gained the support of Henan’s governor and 100 elites from across China visited him. He mediated some tensions between former subordinates. This helped pave the path for his re-emergence after the Wuchang uprising in October 1911.

In 1911, Zaifeng created a cabinet. By selecting nine Manchu nobles among its 13 members, he disappointed Han Chinese observers. Also, that year, some provincial railways went into bankruptcy. In May 1911, the Qing court planned to nationalize them and pledge them as security for more foreign loans for the national government.

A Railway Protection Movement gained support in Sichuan province. The railway there had been funded through a 3% tax on harvests, collected from landlords in exchange for shares in the project. When the Qing planned to nationalize the insolvent railway, it would only compensate investors with bonds and not silver and only partially. The amount offered in Sichuan was lower than in other regions. In August, there was a large demonstration against the proposal and strikes and boycotts.

On September 1st 1911 the railway asked the public to withhold remittance of grain taxes to Beijing as pressure. Local troops opened fire on demonstrators and the situation worsened. The capital replaced the governor and offered full compensation for the railway shareholders, but by then 100,000 armed rebels were causing trouble in the province.

Incidentally, only in 2012 was the final stretch of that planned Chengdu- Wuhan railway completed, more than 100 years after the 1911 revolution. The cities were connected by railway in 1979, but through an indirect route. Now, there is finally a direct connection. Some foreign creditors, including at least 300 Americans, have never had those railway bonds issued by the Qing in 1911 redeemed.

New army troops were sent from Hubei province to suppress the troublemakers and to restore order. This decreased the number of troops in Wuchang, which opened the door for a mutiny and revolution in that city on the Yangtze River.

Newspapers and radical students in Hubei and Hunan provinces criticized elites there and stated that the Qing dynasty was falling and should fall.

On October 9, 1911, a revolutionary was injured making explosives in the Russian concession of one of the three cities that now make up Wuhan. Hospital staff alerted the authorities. The Viceroy ordered arrests and revolutionaries in the Wuchang garrison, expecting a crackdown, staged a mutiny on October 10th. They captured the Viceroy’s residence, but not him. They took some other strategic locations and killed more than 500 Manchu soldiers and captured others. By the next day, a military government had been proclaimed.

Yuan heard about the Wuchang Uprising on his birthday: October 12. Within days, the court had sent an imperial edict appointing him as governor general of Hubei and Hunan provinces, tasked with suppressing the revolution, but only with provincial forces. Zaifeng was not allowing him to use the New Army from north China that Shikai had built up. They were sent south under a Manchu noble.

Shikai’s response was that he needed to recover his health and took two weeks before leaving for his new assignment. He made military requests to the court. In his view, “if I go to Hubei now, I do not even have any land to rest my feet on and I do not have any troops under my command.” “With... empty hands and bare fists, how could I exterminate the rebels?” The Hubei army was on the revolutionary side and the local treasury had been seized. Yuan made requests relating to recruiting soldiers, sub commanders and aid for famine relief.

Some of Yuan’s relatives told him that the national situation could not be salvaged. But Yuan wanted to do his duty.

Why was he brought back by Zaifeng? It seems that the Qing had little choice. They had no strong Manchu military commander. And Yuan still had supporters in the government.

Upon his return, one commentator observed that many outcomes were possible. Yuan could launch a northern expedition to overthrow the Qing. He could be murdered by his soldiers, who would join the revolution. He could defeat the revolution and become emperor. Or he could defeat the revolution selflessly like Zeng Guofan did to the Taiping. It is telling that observers believed the end of the Qing was a real possibility and may have put the odds around 75%.

In early November 1911, Shikai arrived at the frontlines and to bolster morale, visited troops in hospital. He gave them silver dollars and requested nutritional meals for them. His concubine gave them fruit, candies and other gifts. The soldiers appreciated the attention.

Yuan was concerned with foreigners’ neutrality, the number of provinces declaring independence and his weakness in the rear along the rail line to Beijing.

Revolution had spread to the Beijing -Tianjin area and Yuan did what he could to stabilize the situation near the capital. The assassination of a revolutionary division commander was one move.

The officials and elites along the Yangtze were not cooperating and weren’t providing Shikai with resources or information.

His soldiers were loyal to him and launched an attack on part of Wuhan on the north bank of the Yangtze river. The revolutionaries resisted and Yuan ordered fires to be used. Whole neighbourhoods were razed and locals mistreated. Shikai disciplined some of his troops for excesses but the northern bank was secured. His report to the capital said that he only lost 70 troops to the rebels 600. He was elected Premier by the cabinet. Zaifeng soon retired and Shikai had gone from retired to Premier of China in a few weeks.

In November, Yuan pressed on towards Hanyang, a different part of Wuhan on the north shore of the Yangtze River. It was separated by the small Han river from the area he had already taken. He had bridging equipment from Germany. His soldiers did take it after some weeks of urban combat, but it was costly. Shikai had lost over two thousand men. The revolutionaries lost even more.

This costly battle plus the overall national situation caused him to negotiate. Fourteen provinces and Shanghai had declared independence by now. Manchus were being killed in many cities in China. Some Han Chinese also lived in fear of Manchu retaliation. 150 local peasant uprisings would also take place within a year.

The foreigners were neutral, but were increasingly sending gunboats up the Yangtze towards Wuhan, to protect their citizens. Foreign troops were landing in Tianjin. Yuan was concerned that foreign intervention would make matters worse for China.

The imperial treasury was almost bare. Shikai encouraged Manchu nobles to donate for the war and he and they did. But it was a drop in the bucket. The provinces that had seceded were not remitting taxes to the capital. Yuan decided negotiation was preferable and toned down his rhetoric.

The revolutionaries saw benefit in negotiations too. Sun Yat-sen, for instance, could see over 100,000 dead on the revolutionary side if war continued. The revolutionary army was poorly trained and improvised. They were short of weapons, equipment and funds too. Foreign governments controlled tariff revenues as security for repayment of the Boxer reparations. They weren’t willing to lend to the revolutionary government in Nanjing.

Shikai tried to get the other side to agree to a revised Qing constitutional monarchy with a responsible cabinet, but they would not. They agreed to halt fighting for now but agreed to little else.

Shikai thought that China was not ready for a republic and feared removing the Qing would lead to chaos and foreign invasion. But the revolutionaries were adamant. They would not accept a monarchy and demanded a republic.

It was Wang Jingwei, a revolutionary follower of Sun, who over the course of many conversations in Beijing got Yuan to change his views on a republic. We’ll meet Wang again. He would be on the left of the KMT when Chiang Kai-shek took decisive action against the left wing of his party and the communists. Wang would then collaborate with the Japanese as leader of Japanese occupied China during their invasion around the time of the Second World War. For now, it is worth knowing that Wang had travelled to Beijing to assassinate the prince regent, had been arrested and then released. He had befriended Shikai’s son and visited Shikai’s home many times. That is when Wang slowly changed Yuan’s views on a republic.

Eventually, Shikai stated that China’s future government type should be decided by an elected National Assembly. Monarchy and a republic were both options.

Once Sun became provisional president of the Republic of China, Yuan dropped his intermediary and entered negotiations directly. Shikai was worried by Sun unilaterally setting up a provisional republican government. This created the risk of two Chinese governments, one in the south and one in the north. He did not want China split.

Sun was discussing a northern expedition to overthrow the Qing.

Yuan had his own problems in the north. Manchu leadership wanted to preserve the Qing Empire and would not accept a republic. As Shikai put it, “for negotiations, we are short of words; and for war, we lack military funding as well as serviceable weapons.” Some revolutionary uprisings had begun in the north, but the regime crushed them. Shikai tried to resign, but the court did not accept it. Empress Dowager Longyu offered him the title of Marquis instead. Yuan discussed abdication with her. As Shikai left the Forbidden City, revolutionaries tried to assassinate him. Bombs were thrown and killed Yuan’s chief guard and some other guards. As his cart sped away, two women fired pistols at him. He survived, but he never returned to the Qing court. Court officials interrogated the assassins. Until then, many Manchus had believed Yuan to be a collaborator with the revolutionaries. Now they saw him as being in the same boat as them.

One Manchu noble had suggested that he replace Yuan as head of the cabinet. In late January, that young noble was mortally injured returning from a meeting. His death scared the remaining Manchu nobles, who began to see peaceful abdication as preferable to futile and deadly resistance. Even in the north, public opinion was turning against the Qing. Chinese ambassadors overseas were calling for imperial abdication.

Around 47 military commanders sent a public telegram calling for abdication. Many of these had been trained under Shikai’s reforms. The court stalled and the officers sent a second telegram 11 days later. That one stated that the emperor’s life was in danger and that the army might need to march to Beijing for face-to-face talks. They were serious.

There was genuine support for Yuan Shikai to lead the new China. The army was comfortable with that, as were the foreigners. Sun Yat-sen had already offered to give him the presidency in exchange for imperial abdication and agreement on a republic.

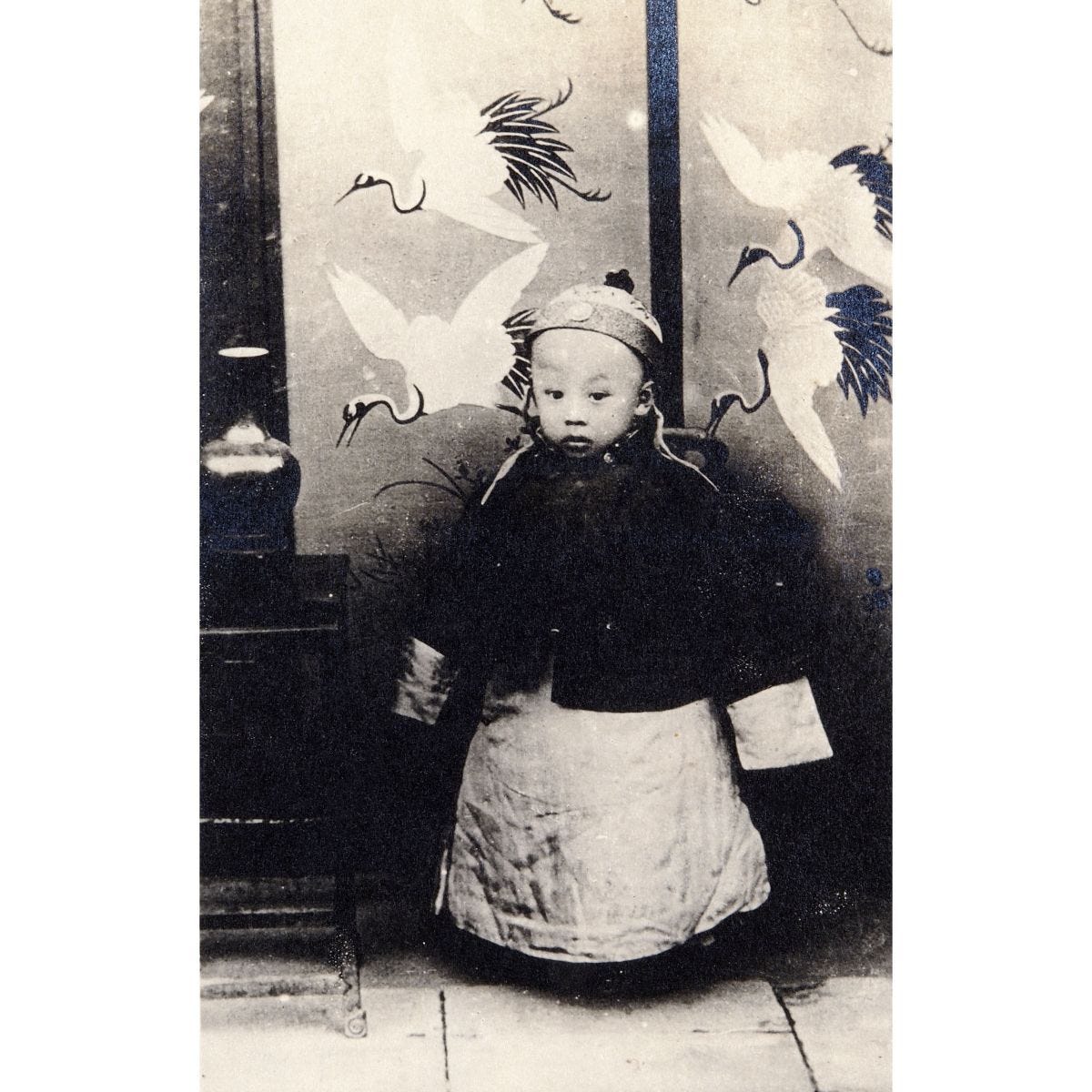

Yuan negotiated favourable abdication terms for Pu Yi. The little emperor would retain his title, receive a generous subsidy and be able to continue to live in the Forbidden City. The Republic of China was proclaimed by imperial edict, edited by Shikai himself. He countersigned the emperor’s abdication.

Shikai sent a telegram to Sun Yat-sen. In it, Yuan wrote “The day of the proclamation of the edict shall be the end of Imperial rule and the inauguration of the Republic. Henceforth we shall exert our utmost strength to move forward in progress until we reach perfection. Henceforth, forever, we shall not allow a monarchical government in our country.”

There would be a brief honeymoon period. All sides celebrated the end of the Qing dynasty in a relatively bloodless way. The world’s most populous country had ended 2000 years of imperial dynasties, formed a modern government, kept the country more or less whole and suffered only minor casualties.

But soon would come what Mike Duncan in his Revolutions podcast series calls the Entropy of Victory. Many factions agreed that the Manchu empire needed to go. Now that victory had been won, the real differences would come out. As for what exactly would replace the Qing, there were a lot of different ideas out there. The honeymoon period would end soon.