Life Under Japanese Occupation

Puppet Regimes in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War (World War II)

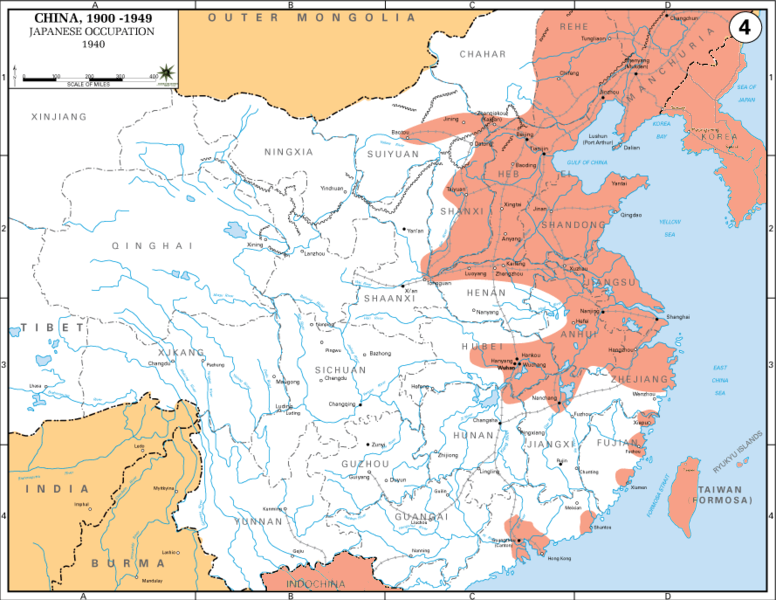

Recently, I’ve described how Nationalist China defended against Japanese aggression and moved inland. I talked about what was happening among the Communists in Yan’an, including the building of a cult of personality around Chairman Mao. I now want to talk about a third area of China: the Chinese who lived under Japanese occupation. More than 200 million Chinese lived directly or indirectly under Japanese control by the late 1930s and early 1940s. Let’s now look at their experience.

Zhou Fenying was born in 1917. In 1938, after the Japanese troops conquered her village, she and her cousin were captured. Fenying was about twenty-one years old. They were taken to the nearby town of Baipu, part of a city in Jiangsu Province.

Fenying and her cousin were then locked inside of a hotel by Japanese troops. They were with girls kidnapped from other nearby villages.

Fenying recalls that each of the girls was given a number, printed in red on a piece of white cloth. They were then treated like numbers and not like humans. They had no freedom at all. They experienced starvation and terrible sanitation. It was like prison. When she saw Japanese soldiers approaching the hotel, she became very frightened. She could not stop crying and fell into a trance. She almost passed out and a Japanese soldier raped her. For months to come, the assaults happened regularly. This mistreatment haunted Fenying for the rest of her life. That was her experience of being a Chinese “comfort woman”.

Lei Guiying wrote a book called Chinese Comfort Women that included her story. She was born in Guantangyan. In 1937, “Having neither a job nor home, I wandered the streets of Tangshan begging. An old woman said to me: “Girl, I know a place where you can have meals to eat. You just have to do some work.” She told me the place was called Gaotaipo. It was owned by a Japanese couple named Shanben. I didn’t know that place was, in fact, a military brothel until much later. I had no idea that it was a comfort station, nor did I know what a comfort station was at that time. …I turned thirteen in 1942 and I began menstruating that year. Mrs. Shanben smiled at me. ‘Congratulations!’ She said, ‘You are a grownup now.’ I remember that it was a summer day and a lot of Japanese troops came to the Shanbens’ house. I saw them picking out good-looking girls and mumbling something. Mrs. Shanben told me to change into a Japanese robe that had a bumpy sash at the back and to go to that large room. Before I could figure out what was going on, I was pushed over to the Japanese soldiers. I was frightened. A Japanese soldier pulled me over, ripped off my clothes, and threw me on the wide bed. I resisted with all my strength. My wrist was injured during the fight and the wound left a scar that is still visible now. The Japanese soldier pressed my belly with both of his knees and hit my head with the hilt of his sword while crushing me under his body. He raped me.” Guiying was thirteen years old then.

A major historical study of the military comfort women system determined that there were 360,000 to 410,000 comfort women in Japanese occupied territories. Chinese women, at about 200,000, were the largest group among them.

As I mentioned during the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Rape of Nanking, not all these girls and women survived the war. Many were killed too.

Before I explore more about life under Japanese occupation in mainland China, let’s look at life under Japanese rule in Taiwan.

Japan controlled Taiwan longer than it did Manchuria or coastal China. Taiwan was a Japanese colony for 50 years, compared to around 14 years of Japanese military dominance in Manchuria and even less for eastern China.

Japan acquired legal authority over Taiwan and the Penghu Islands in the Treaty of Shimonoseki at the end of the first Sino-Japanese war. There was local armed resistance to the Japanese takeover, both immediately after the handover as well as during the first decades. Some residents left Taiwan rather than live under Japanese rule.

To build its control, Japan did a detailed land survey almost as soon as it took possession of Taiwan. While Qing land registers only showed 867,000 acres of land yielding revenue, Japan determined that the correct amount should have been 1,866,000 acres. Japanese officials therefore quickly doubled the amount of land paying tax.

The land holding system was also simplified. Under the Qing, tenants paid rent to small rent holders who then paid rent to an even smaller number of great rent holders. The Japanese eliminated the great rent holders by providing them compensation. This simplified the land holding system so there was only one owner of each property, instead of two holding different rights. Japan then taxed the one owner, who could collect rent from a tenant if the land was rented out. At the time of that change, there were about 750,000 tenants, 300,000 small rent holders and 38,000 great rent holders. It was those 38,000 who were compensated, and their rights abolished.

The Japanese authorities took data collection seriously. There was a regular census in 1915 and the night before the census, trains were full of passengers returning to the place they had registered before the census. The rumour going around was that anyone who wasn’t home when the census officials came, and asked questions would be considered a “bandit”. People were rushing back home to avoid the consequences of potentially being deemed a bandit.

Japan’s census in 1905 was the first time that a detailed population figure had been calculated in Taiwan. The Qing had estimated the population. The Japanese came up with exact numbers, including a break down by gender (112.7 men for every 100 women) and an average of people per household (6.2).

The Japanese also developed Taiwan. They worked to eradicate diseases like cholera. They widened narrow paths into roads. They laid railway track and developed ports. By the end of the war, many of them were bombed by US planes, attacking Japan’s military-industrial system. Between 15,000 and 30,000 residents died from the bombing.

With the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan started an “imperial subject movement” to make the Taiwanese more Japanese. In 1937, Japan claimed it was creating a “New Order in East Asia”. That then evolved to a “New Order of Greater East Asia”. In 1940, the term “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was introduced. In this Japanese colony, as elsewhere, the Japanese were on top, and the Han Chinese and indigenous residents did not equally share in this “Co-Prosperity Sphere”.

Administrators encouraged changes to customs like weddings, funerals, and festivals to be more Japanese. Locals were even encouraged to change what kind of bed they slept on. Interestingly, to me at least, one of the local habits that the Japanese wanted to end was the so-called “old culture of individualism”. The Japanese thought that the ethnically Chinese were too individualistic and needed to increase their sense of public spirit.

Early on during the Japanese colonial period, publications had blossomed. The first newspaper to be published in Taiwan started soon after Japanese rule. There was a period of a relatively free press, with open criticism and parodies of the colonial government. But by the time of the war, censorship and restrictions were widespread.

During the war, newspapers and publishers stopped printing in Chinese with very few exceptions. Any teaching of Chinese in public schools was ended. If you were school aged during the Second Sino-Japanese War, there was no option of learning Chinese in school. Teaching was in Japanese.

By the end of the war, perhaps 57 people in a hundred understood Japanese, with a doubling during the war. Before that, the primary languages spoken were what some call Taiwanese, but is also called Hokkien, a speech also common on the Fujian coast where a lot of the residents of Taiwan had emigrated from. There were also Hakka speakers, who had originally come from Guangdong province. Taiwan also has important but small indigenous populations. Traditionally, many of them lived in the mountains.

Taiwan was increasingly industrialized to support the Japanese war effort and by 1939, industry was more important than agriculture in the Taiwan economy. These modern industries had Japanese owners.

Civilian leadership was replaced by military leadership. The Japanese navy operated from Taiwan. Taiwan was an important staging location for the Japanese attack on Guangdong and Hainan Island during the war. Air operations flew from Taiwan, including for the Japanese takeover of the Philippines.

Ethnic Chinese residents were mobilized to support the Japanese war effort. There was even a name change campaign to get families to change their names to Japanese ones. Officials gave material benefits during the war to those that changed names, but still only a small percentage changed to a Japanese name.

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Hong Kong, the International Settlement in Shanghai and elsewhere beginning in December 1941, the Japanese encouraged the locals to join them in fighting the British and Americans.

Early in the war, the authorities requisitioned labour and recruited. In April 1942, the “Army special volunteer system of Taiwan” was instituted. The next year, the “Navy special volunteer system” was also created. Propaganda promoted “glorious military labourers”. Japan’s two earliest colonies, Taiwan and Korea, had a combined population equal to 25 people for every 100 in Japan. So, boosting Japan’s effective population by a quarter was important during the war. Over 200,000 residents of Taiwan served the Japanese military directly. In the early years of the war, usually in labouring rather than military roles. They had titles like “military porter” and “attached civilian”. There was finally conscription or summons too.

The Japanese in Taiwan used the traditional Chinese Baojia system of control. That is where a group of 10 households were bound together. If one household failed to do what was required, such as paying taxes, then all 10 households would be punished. It helped to control all levels of society. This seems to have been used in the puppet regimes in mainland China too. A similar system has received endorsement from today’s Communist Party in China, including from Xi Jinping.

After September 1943, the Japanese government ordered that villages would allot the expropriation burden for each family. The village-level organizations became the units that shouldered Japan’s wartime grain quotas. This ensured expropriation from farm families and fine-tuned adjustments.

The traditional structure rested on strict mutual surveillance to ensure that, however poor a villager was, he had to rely on adjustment within the village and act as a part of the village, not engage in selfish deviations. This method worked better than what the Nationalists imposed in China during the war. Their organization at the village and local level was much less effective and more impacted by village elites exempting themselves from food or conscription drives and imposing them instead on the least powerful.

In the bureaucracy, Taiwanese were predominantly clerks. Few Han Chinese or indigenous people served in higher positions, which were mostly held by ethnic Japanese.

The Japanese led the opium trade in Taiwan until the summer of 1945. Although under pressure, they had also made efforts to decrease permits for opium sales and had opened a rehabilitation clinic and launched an anti-drug campaign.

Some women from Taiwan were made to provide sexual services during the war as so-called Comfort Women. Some were recruited for what they thought would be housekeeping, laundry or nursing services only to later learn they would be used sexually. Some were financially desperate or were sold by their families. They were sent overseas. Around 1940, brothels were also set up in Taiwan for Japanese soldiers.

Taiwan, under Japanese rule, like the puppet governments on the mainland, had its own Central Bank which issued and managed its currency.

At the Cairo Conference in 1943, Chiang Kai-shek was able to get the allies to agree that Taiwan, the Penghu Islands (also known as the Pescadores), as well as Manchuria, would be part of the Republic of China following the defeat of Japan. Chiang met with US President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in Cairo who then made the Cairo Declaration announcing this intention.

Once Japan’s surrender was news, but with Japanese officials still in charge of the island for a brief time, there were documented cases of violence by locals both against Japanese policemen and against some ethnically Han officials. Grievances sometimes turned violent during Japan’s lame-duck period between surrender and leaving Taiwan. Many of those attacked seem to have been involved in mobilizing labour during the war. In August 1945, at the time of the Japanese surrender, an issue was reimbursing labourers for work during the war. Some of that frustration over back pay turned violent once locals no longer feared the old authorities in the same way. Some still claimed unpaid wages from Japan decades later, without success.

When the Republic of China took control of Taiwan in late 1945, they instituted Mandarin as the national language and soon thereafter banned Japanese. There was some local pushback as residents felt the changes were too fast.

Mainland scholars today refer to the education system under Japanese rule as “enslaved education”. Right after the war, that was what the KMT called it too. But many Taiwanese disputed that term, especially in the education field. Those people didn’t think the education system had enslaved them. Some believed there had been some value in the Japanese education system, even if the Japanese occupation itself could not be defended. It is said that Taiwan had the second highest primary school enrollment rate in Asia, second only to Japan. There had, however, been limited education options in Taiwan after primary school. The Japanese didn’t want ethnic Chinese to be too educated, except perhaps for some collaborating elite families. After the handover of Taiwan to the Republic of China, around 300,000 Japanese were ordered to leave, including many who were born in Taiwan. There were rules on what the Japanese could take with them. Many left voluntarily without much trouble.

Manchuria was next in experiencing Japanese domination. Japan’s Kwantung Army had been in Manchuria since the Russo-Japanese War. It was originally to protect Japanese controlled ports and railways. As I’ve previously mentioned in the episode, Japan Attacks, the Kwantung Army seized control of all of Manchuria starting in 1931 and then set up the so-called puppet state of Manchukuo with Puyi as Emperor. From the beginning, the Kwantung Army was actively pulling the strings.

It was the Japanese military itself, more so than the government in Tokyo, that spearheaded this process. The takeover of Manchuria was the result of action within and by the Kwantung Army. Governments in Tokyo reacted either to try to rein in or support the Kwantung Army. Tokyo did not lead the process that created Manchukuo. The cabinet in Tokyo was the follower of its own army in Manchuria.

Since Manchuria had a different history than Taiwan, the experience of the locals was also different.

One terrible part of the Chinese experience of Manchukuo, was Unit 731. Established in 1936, Unit 731 operated a bit south of Harbin. Today Harbin is known for its beautiful ice sculptures and winter tourist attractions. Unit 731 was a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Kwantung Army, which itself was part of the Imperial Japanese Army. It conducted lethal human experimentation and biological weapons manufacturing. Unit 731 was responsible for some of the most notorious war crimes.

It routinely conducted tests on people who were gathered from the surrounding population and dehumanized. Test subjects were sometimes referred to as "logs", used in such contexts as "How many logs fell?" This term originated as a joke because the official cover story for the facility was that it was a lumber mill. Researchers in Unit 731 also published some of their results in peer-reviewed journals, writing as though the research had been conducted on so-called "Manchurian monkeys".

Experiments included disease injections, controlled dehydration, biological weapons testing, hypobaric pressure chamber testing, vivisection without anesthetic, organ harvesting, amputation, and standard weapons testing. Victims included kidnapped men, women (including pregnant women) and children and also babies born from the systemic rape perpetrated by the staff inside the compound.

Most, but not all, of the victims were Chinese. Originally set up by the military police, Unit 731 was taken over and commanded until the end of the war by General Shirō Ishii, a combat medic officer. It was like Dr. Mengele’s medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz.

Unit 731 produced biological weapons that were used in areas of China resisting Japan, including Chinese cities and towns, water sources, and fields.

Changde was one of the sites of Japanese plague flea bombing. Later, in 2002, it was the site of an "International Symposium on the Crimes of Bacteriological Warfare". It estimated that the number of people slaughtered by the Imperial Japanese Army germ warfare and other human experiments was around 580,000. An American historian states that over 200,000 died.

In addition to Chinese casualties, 1,700 Japanese troops in Zhejiang were killed by their own biological weapons while attempting to unleash them. This shows the risk, even to their own side.

An assistant recalled that Yoshio Sudō, an employee of the first division, became infected with bubonic plague during the production of plague bacteria. The Special Team was then ordered to vivisect Sudō. That means he was cut while alive.

I could go on, but I think you understand what kind of place it was.

When the war was ending, the remaining prisoners were given the option of suicide, which 25% selected. The others were killed by potassium cyanide or chloroform. Unlike Auschwitz, no prisoner who entered Unit 731 came out alive.

Twelve members of the unit were tried and sentenced in Soviet war crimes trials after the Soviet Red Army invaded Manchuria and defeated the Japanese Kwantung Army.

In Manchuria, Japan also established a monopoly for the opium trade and increased production and distribution of opium and other narcotics. Golden Bat cigarettes were laced with opium. Golden Bat was only one of the products of the conglomerate Mitsui, which seems to have been heavily involved in the opium trade, especially targeting Chinese. Suspiciously, these cigarettes were not allowed to be sold in Japan and were only available for export. Imagine you lived in Manchuria during the occupation and were a smoker. If you grabbed a pack of the least expensive Japanese made cigarettes, you would unwittingly be exposed to addictive opium.

Imperial Japanese Army general Kenji Doihara was part of that plan of lacing cigarettes with narcotics. He was later convicted and sentenced as a war criminal in Tokyo in 1948.

Japanese opium policies not only devasted Chinese people. They were also important sources of revenue.

One of Japan’s goals for Manchuria was to be home to Japanese to deal with the problems of overpopulation and lack of arable land in Japan. Land-poor farmers from its inner islands were relocated. By 1945, over a million Japanese people had settled in Manchukuo. They then moved the other way at the end of the war.

They disrupted the existing social fabric. Japanese settlers often received fertile land, at the expense of locals. This fueled resentment.

During the Japanese occupation, Manchuria became a significant producer of soybeans, wheat, and other staples.

Manchuria was rich in natural resources. Japanese companies exploited coal, iron, other minerals, and timber.

Japan set up steel mills, cement factories, and machinery plants. These industries supported Japan’s war efforts and industrial growth.

Textile mills produced silk, cotton, and wool fabrics.

Japanese banks and trading companies set up branches in Manchukuo.

Like in Taiwan, Manchukuo had policies controlling movies, literature, and news media. They were of-course pro-Japanese cultural policies. They also restricted dark or negative themes in literature and controlled narratives about women. Japanese Imperial Policy, which extended through the Manchukuo state, stressed that women should serve traditional roles as wives, mothers and cooks. Some ethnically Chinese intellectuals in Manchukuo resisted the official rules and wrote works that were dark and spoke to the hopelessness of those times. Others, especially women writers, chose to focus on themes of rape, betrayal, and a need for women to be independent. In the early years of Manchukuo, some of their works escaped censorship because of their low profiles as female writers. But as the war progressed, censorship was increased, and authors and intellectuals were punished for works contravening official guidelines. Later, these same authors who had been punished by the Japanese dominated regime were punished again by Communists for allegedly collaborating with the traitors because they had stayed in Manchuria rather than flee to Communist held base areas. New censorships were imposed, and many authors found it more difficult to distribute work under communism than under Manchukuo’s system.

In addition to Manchukuo, the Japanese Army in North China set up an additional puppet regime: the Political Committee of North China and then the Provisional Government. Wang Kemin was the top leader of the puppet regime in North China. The Japanese Central China expeditionary forces authorized a further Chinese puppet government, the Reformed Government of the Republic of China in Nanjing. Its figurehead was Liang Hongzhi, who had been part of the Anhui Clique during the Warlord Period. It eventually evolved into the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China, led by Wang Jingwei, who was a KMT official that I have mentioned multiple times in previous episodes. There was also a so-called autonomous government in Inner Mongolia, known as the Mongol Military Government.

The puppet regime in North China, known as the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, copied the political system of the Beiyang government (the Republic of China government system as exercised by Yuan Shikai and his successors prior to Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Expedition). Politicians from the old Beiyang government took roles in the regime, which was under Japanese control and they are generally considered to have been traitors and collaborators. Japan’s goal was to control China, use its resources and subdue the Chinese inhabitants. Having some previously high-ranking Chinese officials as figureheads served some purposes for Japan as it made the new situation seem more like an evolution of the old government. It existed from 1937 to 1940. After that, it was officially merged into the Reorganized Government led by Wang Jingwei. The North China regime’s influence, whatever it was, was limited to larger cities and railways where Japanese military control extended. The more remote areas of the countryside were not really under Japanese or the regime’s control. This Provisional Government gave extensive powers to its Japanese advisors and never sought international recognition, even from Japan. When it ended in its merger with the Reorganized National Government out of Nanjing in 1940, Wang Jingwei never really had control in north China. The Japanese military there retained real control.

There was also a puppet regime operating from Nanjing as the Reformed Government of the Republic of China after Japan seized Nanjing and other areas along the coast and the Yangtze River. It existed from 1938 to 1940, when it and the North China Provisional Government became part of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China, which was founded in March 1940 and only ceased to exist with Japan’s surrender in 1945.

Next time, I’ll look at Wang Jingwei, the KMT official, and his decision to defect from the Nationalist government in Chongqing and to lead that Reorganized government in occupied Nanjing, allied with the Japanese. Please join us for that.

P.S. Did you know that The Chinese Revolution is on YouTube and is also a podcast?

Thank you for sharing this history. It's a lot to process. my cousin was an AVG Flying Tiger in 1941-1942 so I have a vague understanding of what was happening in that time period in China and Burma. Now that I'm researching the history of an American who was a Japanese POW for 3 years, understanding more of the context of what was happening in this area is important.